Preface to a Commentary on the Gospel of Thomas

Several years before the advent of the common era, about 380 years after the final emancipation (parinirvana) of the Buddha, according to current scholarship, a great bodhisattva was born in the outlying region of Galilee to the north of Judaea by the name of Yēšūaʿ (Joshua or “Jesus”). Galilee was notorious amongst the more orthodox and xenophobic Jews to the south for foreign influences and mystical cults, as well as populist Jewish rabbis who were reputed as wonder workers, leading to the famous quip, “Can the Messiah come from Galilee?” (John 7:41; cf. John 1:46). Little is known of Yēšūaʿ’s childhood or early adult life, but it is generally believed that he emerged from obscurity in his early 30s, quickly achieved fame as a teacher and psychic healer, travelled to Jerusalem, and was crucified by the Roman authority on the hill of Golgotha outside the Jerusalem gate, perhaps in 33 CE. After Yēšūaʿ’s death many traditions began to circulate concerning his life and work, and over time his fame spread to Rome and beyond, largely as a result of the proselytizing work of his disciples. The familiar synoptic gospel accounts of Matthew, Mark, and Luke were probably composed in the late first century CE. The earliest was the Gospel of Mark, composed between 60 and 70 CE, some 30-odd years after Yēšūaʿ’s death. These gospels, plus John, which was written between 90 and 100 CE, became the basis of the orthodox Christian account of Yēšūaʿ’s life, works, and teachings according to the Roman Church, which condemned all other accounts as heresies and actively persecuted them and their successors over many centuries, especially after Theodosius made Nicene Christianity the official state religion of Rome in the late 4th century CE. However, we know that many other accounts of Yēšūaʿ existed contemporaneously with the canonical texts. The four gospels that finally came to be accepted as “canonical” were themselves selected from a large number of alternative scriptures, largely for political, theological, and numerological reasons. Most scholars believe that the canonical gospels themselves are based on more primitive collections of sayings of Yēšūaʿ that preceded the more developed historical accounts, including an hypothesized text called Q, which can be reconstructed from the synoptics but has never been found.

This was the state of affairs until 1945 CE, when a forgotten cache of buried manuscripts was discovered in a cave in the Egyptian desert near Nag Hammadi. These became known as the Nag Hammadi library, and have since been translated and published. The Nag Hammadi library consists of 52 tractates termed “gnostic” dating from the second century CE, i.e., hardly more than a century later than the canonical gospels. There is, moreover, no reason to believe that these tractates are original. Therefore, at least some of them are probably contemporary with the canonical gospels and some may even be older. Of particular interest in this regard is the Gospel of Thomas, which consists of a collection of 114 sayings attributed to Yēšūaʿ. Like the hypothetical Q, Thomas is a sayings gospel,[1] and about half of the sayings are similar to sayings also found in the canonical gospels, but the point of view is very different. According to some scholars, including the translators of the Annotated Scholars Version (ASV) of the gospels, Thomas may have been composed as early as 40 CE, less than ten years after the crucifixion and at least 20 years earlier than the earliest canonical gospel.

No one can say with certainty that the sayings of Thomas or, indeed, those of the canonical gospels are identical with the words of the historical individual known as Yēšūaʿ, but Thomas and the Nag Hammadi library attest to the fact that a gnostic or proto-gnostic spiritual interpretation of the teachings of Yēšūaʿwas prevalent in the early Christian community almost contemporaneously with the crucifixion or very shortly afterward. This effectively refutes the dogma that Gnosticism is a later aberration from an original orthodoxy that all contemporary Christian churches since the time of Irenaeus (fl. ca. 130 CE) claim for themselves and which the Roman Church used to justify the virtually total destruction of the original gnostic writings which, except for a few fragments, were lost to history for almost 2,000 years.[2]

The existence of a secret teaching is attested in the canonical gospels themselves, as follows:

And his disciples approached and they were saying to him, “Why are you speaking with them in parables?” But he answered and said to them: “It has been given to you to know the secrets of the Kingdom of Heaven, but to them it has not been given. For to one who has it, it will be given, and it will be increased. And from him who has it not, will be taken even that which he has, therefore I am speaking to them in parables because they who see do not see, and those who hear neither hear nor understand. And the prophecy of Isaiah is fulfilled in them, which says, ‘Hearing you will hear, and you will not understand, and seeing you will see and you will not know. For the heart of this people has become dense, and they have hardly heard with their ears and their eyes they have shut, lest they would see with their eyes and they would hear with their ears and they would understand in their hearts and they would be converted and I would heal them.’ But you have blessings to your eyes, for they are seeing, and to your ears, for they are hearing. For I say to you that many Prophets and righteous ones have yearned to see the things that you are seeing and they did not see them, and to hear the things that you are hearing, and they did not hear them. (Matthew 13.10-17)

Yēšūaʿ said to them, “It has been given to you to know the secrets of the Kingdom of God, but to outsiders, everything has been in parables. So that seeing they shall see and not see, and hearing they shall hear and they shall not understand, unless perhaps they shall be converted and their sins shall be forgiven them.” (Mark 4.11, 12)

But he said to them, “It has been given to you to know the secret of the Kingdom of God, but to those others, it is spoken in an allegory, that while seeing they will not perceive, and when hearing, they will not understand.” (Luke 8.10)

Thus it appears that Yēšūaʿ was a wisdom teacher and wonder worker typical of Galilee, as discussed above, who was popular with the people but resented by the reactionary Jewish authorities of Jerusalem who instigated the Roman authority against him, apparently on trumped up charges of sedition. Yēšūaʿ’s crucifixion too was typical of the time. The Jewish historian Josephus says that the Romans crucified nearly 10,000 people just in Jerusalem in reaction to the numerous rebellions before 70 CE. Some say as many as 200,000 Jews were crucified in all of Palestine. It comes as no surprise then that the crucifixion of Yēšūaʿ was hardly noticed at the time.

One of the most remarkable things about the Gospel of Thomas is its spiritual interpretation of the teachings of Yēšūaʿ, expressed in terms strikingly similar to the teachings of the Buddha preserved in the Pali Canon, which were not written down until the first century BCE. Although Buddhism eventually penetrated as far west as present-day Afghanistan, it is unknown whether the Buddhadharma actually influenced Yēšūaʿ in an historical sense.[3] Nevertheless the language of the Gospel of Thomas is strikingly similar to the dharma of the Buddha. Centuries later, Gnosticism also influenced the great 8th century Tantric adept Padmasambhava, who was probably born in the border area of what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan. This concurrence of language and theme, even though Yēšūaʿ was a theist, is a striking confirmation of Yēšūaʿ’s originality and the profundity of Yēšūaʿ’s spiritual reinterpretation of Judaism, which was almost lost to history. For this reason we may regard Yēšūaʿ as a true Jewish bodhisattva and his life and teachings a testament to the universal validity of the dharma.

The Gospel of Thomas is remarkable not only for what he does say, but also for what he does not say, for Thomas does not refer to the virgin birth, miracles, the resurrection, or the doctrine of vicarious atonement—all cornerstones of the canonical gospels and pillars of what became the orthodox religion that opposed and very nearly destroyed the spiritual tradition represented by the Gospel of Thomas.

Despite its brevity, the Gospel of Thomas is certainly one of the great works of world spiritual literature. Its discovery may yet herald a second reformation of the Christian religion, after the long dark age from which the West has still not emerged. The commentary that follows explores these similarities by comparing the teachings of the Buddha with those of Yēšūaʿ as preserved in the Gospel of Thomas.

Notes

- The Nag Hammadi library includes four gospels—the Gospel of the Egyptians, the Gospel of Philip, the Gospel of Thomas, and the Gospel of Truth—but only one, the Gospel of Thomas, is a sayings gospel. Some scholars have suggested that Thomas might even be Q!

- The Early Christian Writings website has a list of about 150 early Christian writings from 30 to 400 CE, in chronological order. What is very interesting about this list is the number of non-canonical works that are contemporaneous with the accepted canonical writings. In fact, the Gospel of Thomas is the earliest gospel in the list, predating the Gospel of Mark by 25 years!

-

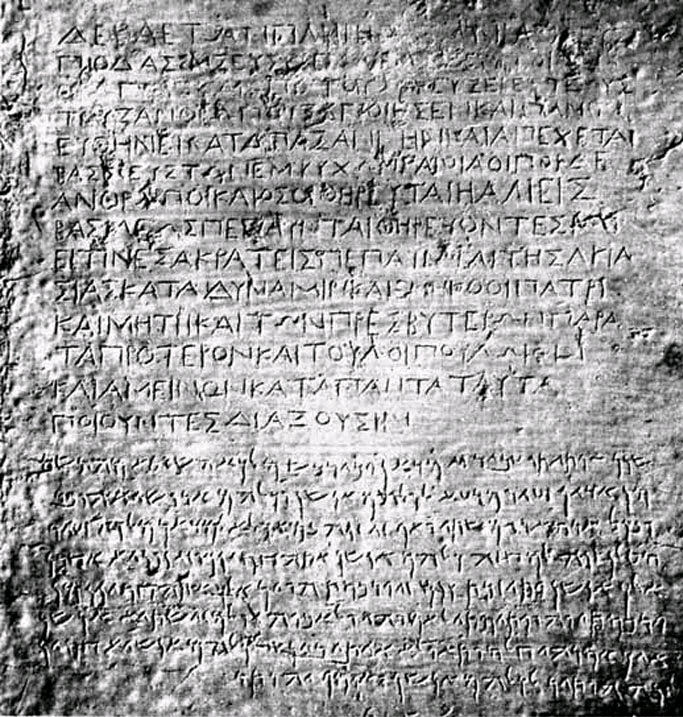

Ashoka, the Mauryan emperor who ruled much of the Indian subcontinent in the 3rd century BCE, sent Buddhist emissaries far beyond India’s borders—including to regions of the Near East and the Hellenistic world. Some of his edicts were written in both Aramaic and Greek, indicating contact with and concern for populations speaking those languages. These edicts suggest at least the potential for the transmission of Buddhist ideas westward. Buddhist communities are reported to have existed in Alexandria during the Hellenistic period, and the pre-Christian ascetic group known as the Therapeutae, described by Philo of Alexandria, shows notable parallels with Buddhist monastic practices, particularly in terms of simplicity, celibacy, meditation, and contemplative withdrawal from society. Although direct historical linkage cannot be proven, the similarities have led some scholars to suggest possible Buddhist influence, or at least a shared religious environment in which Buddhist and Hellenistic ascetic ideals converged. A Buddhist embassy may have reached the Roman world during the reign of Augustus, between 22 BCE and 13 CE, as recorded by Greek sources such as Strabo. While the details are sparse, such an event would confirm a known cultural awareness of Buddhism in the Mediterranean world before or during the early life of Jesus. Galilee, where Jesus lived and taught, was a region of considerable cultural mixing and had exposure to foreign influences through trade and travel routes. In light of the above and given the remarkable number of parallels between Buddhist and Christian teachings—particularly in parables, ethical teachings, and themes such as compassion, nonviolence, detachment, and the illusory nature of worldly wealth—it is plausible, though not provable, that Buddhist ideas or motifs may have influenced Jesus, either directly or indirectly through the intellectual and spiritual crosscurrents of the era.

Bibliography

Annotated Scholars Version.

Bauscher, Glenn David. The Original Aramaic Gospels in Plain English. N.p.: Lulu Publishing, 2008. www.wisdomintorah.com. May 4, 2013.

Early Christian Writings. http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/ May 4, 2013.

Metalogos: The Gospels of Thomas and Philip and Truth. www.metalog.org. May 4, 2013.

The Nag Hammadi Library. http://gnosis.org. May 4, 2013.

Pali Canon.

YouTube.