The following talk was presented to the Spiritual Arts Growth and Enlightenment Society (S.A.G.E.S.) on Sunday, March 9, 2014, and the Buddha Center on Tuesday, March 11; Saturday, March 15, 2014; and Sunday, March 30, 2014.

In this talk, I will discuss the status of women in pre-Buddhist India as well as the India of the Buddha’s time in order to establish context. I will then critically evaluate the Buddha’s own sexuality and the attitudes to women and sexuality attributed to him in the Pali Canon, especially in the discourses. I will discuss the context in which the rules for monastics were codified in the Vinaya during the First Buddhist Council and later, including the philosophical or “theological” implications of this discussion. Finally, I will conclude with a survey of the status of women in the Buddhist world today and consider the significance of this discussion for the Dharma Transmission to the West.

The Traditional Indian View of Women in the Early and Late Vedic Periods

Indus Valley Civilization (3500–1300 BCE) and Its Cultural Legacy

The ancient Indian—or Harappan—civilization emerged in the late 4th millennium BCE and reached its peak between 2600 and 1900 BCE. Spanning an area of approximately 1.6 million square kilometers, it extended from northeastern Afghanistan in the west to Pakistan and northwestern India in the east. At its height, it supported an estimated population of five million, making it the largest of the three great Bronze Age civilizations, alongside Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The Harappan people developed advanced urban and technological systems: grid-planned cities, multi-storey baked brick houses, complex sewage and drainage infrastructure, public water supply, and large, non-residential public buildings whose function remains unclear but may have been administrative or religious. This was a highly organized and mercantile society, with widespread trade networks reaching as far as Sumer, as attested by the discovery of Indus seals in Mesopotamian sites.

Harappan artisans worked with copper, bronze, lead, and tin, and developed sophisticated techniques in metallurgy and handicraft. Over 2,600 archaeological sites have been identified, although the Indus script remains undeciphered. Many scholars suggest that it is related to the Dravidian language family—a non-Indo-European linguistic group still spoken in southern India and Sri Lanka. This suggests a cultural and linguistic continuity that survives to this day.

While much remains unknown about Harappan religion and society, the evidence we do have suggests a highly stratified but relatively peaceful culture, with no conclusive evidence of standing armies, fortifications, or large-scale warfare. Society appears to have included religious, merchant, and labouring classes. Numerous goddess figurines, often made from terracotta, and the absence of obvious symbols of male dominance have led scholars to speculate about the importance of female deities and the possible social influence of women. The discovery that men may have moved into the homes of their brides—an apparent form of matrilocality—has been interpreted by some researchers as indicating a matrilineal or at least female-positive social structure.

Clay goddess effigies—often crude in workmanship but ubiquitous—suggest the widespread worship of a Mother Goddess figure. According to Gupta (2002), “the Goddess was not favoured by the upper classes who commanded the services of the best craftsmen, but… her effigies were mass-produced by humble potters to meet popular demand.” The sheer number of these figurines implies that this deity was venerated in daily life, likely kept in private homes for purposes of fertility, protection, and household prosperity.

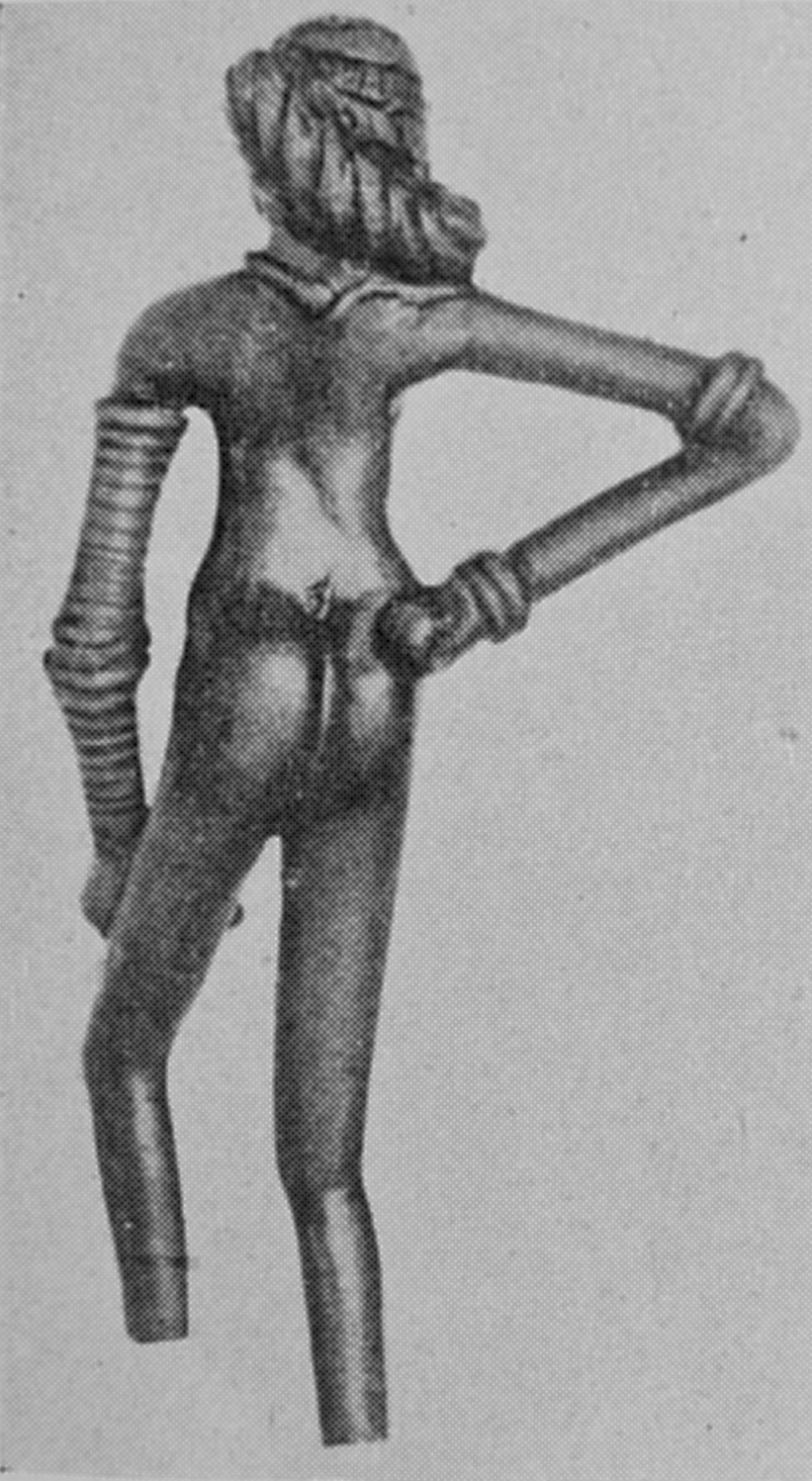

One of the most iconic artifacts is the so-called “Dancing Girl,” a bronze statuette of a young woman, naked except for bangles and a necklace, standing in a relaxed, confident pose with one hand on her hip. Her elaborate coiffure, slender build, and self-assured expression suggest a culture that appreciated both feminine beauty and artistic expression. “Her face has an air of lively pertness quite unlike anything in the work of other ancient civilizations,” Gupta writes, noting that the Harappan aesthetic diverged markedly from that of later, more ascetic Indian ideals.

A particularly significant motif is found on a seal unearthed in the city of Mohenjo-Daro: a horned figure seated cross-legged, surrounded by animals. This image, commonly identified as Pashupati—“Lord of the Animals”—is often interpreted as a proto-Shiva figure. The presence of phallic symbols resembling later lingams reinforces this association. If this identification is correct, the roots of Shiva-Shakti worship may reach back into pre-Vedic times. In later Hindu metaphysics, Shiva represents the male creative principle—life, death, and rebirth—while Shakti, literally “power” or “energy,” is his dynamic consort and metaphysical complement. Without her, Shiva is inert, passive, even impotent. In the human being, Shakti becomes the manifestation of intelligence, creativity, compassion, and divine love.

Although the full flowering of Shaktism as a distinct religious tradition did not occur until around 400 CE, references to Shakti appear in the Rigveda, and goddesses cognate with her appear at least 40 times. Thus, the conceptual and devotional basis of goddess worship in India may stretch back not only to the Vedic period but into the pre-Vedic past, possibly as far as the late Paleolithic. The prominence of female figurines, the apparent respect for women, and the symbolic associations of power, beauty, and fertility all suggest that the Harappans contributed essential elements to the later religious culture of the subcontinent.

In contrast to the patriarchal, martial structures of many contemporary civilizations, the Indus Valley appears to have been relatively pacific, urban, and mercantile. While no direct connection can be conclusively established, the possibility that elements of later Indian religion—especially goddess worship and Shaivism—may be rooted in this ancient, enigmatic culture remains a compelling hypothesis.

Aryan Incursion (1500–1200 BCE)

The decline of the Indus Valley Civilization around 1900 BCE appears to have been the result of multiple converging factors, including climate change, river system shifts, and gradual economic decline. Following this, new groups migrated into the Indian subcontinent, among them Indo-Aryan pastoralist tribes originating from the Central Asian steppe region, possibly near the Caspian or Black Sea. These groups brought with them a patriarchal, horse-based warrior culture, and their arrival over several centuries led to profound transformations in the region’s social, linguistic, and religious landscape.

Rather than a single military “invasion,” the Indo-Aryan migration was likely a complex and prolonged process of cultural interaction, assimilation, and displacement. The Rigveda, the earliest Indo-Aryan religious text, contains poetic references to conflicts with Indigenous peoples which may reflect dim memories of these cultural confrontations. Many scholars now interpret these encounters as ideological or tribal rather than racial, and the term “Aryan” itself, meaning “noble,” was more an ethno-linguistic marker than a racial category.

The earlier Dravidian-speaking populations, possibly descended from the Harappans, were gradually displaced to the south, although significant cultural and genetic continuity between Harappan and later Indian civilizations suggests deep integration as well.

Among the contributions of the Indo-Aryans to early Indian religion was the ritual use of Soma, a mysterious psychoactive plant drink, celebrated in the Rigveda as a divine elixir that conferred insight, strength, and immortality. The exact identity of Soma is unknown, though candidates have included ephedra, Amanita muscaria (fly agaric mushroom), cannabis, or a combination involving poppy derivatives. While speculative, some researchers argue that Soma was a stimulant or entheogen central to early Vedic religious experience. The hymns are said to have been “inspired by Soma,” which was personified as a god and praised in ecstatic poetry.

This period of cultural fusion gave rise to what is now called the Vedic civilization, forming the basis for classical Hinduism and much of Indian religious and philosophical thought to the present day.

Rigvedic Period (1500–1000 BCE)

The idea that women held a relatively high status in ancient Indian civilization—particularly in the Harappan and early Vedic periods—is supported by many scholars, though the extent and nature of that status remain debated. Some researchers argue that the archaeological evidence from the Indus Valley suggests a society that, while not necessarily matriarchal, may have featured more prominent roles for women than later Brahmanical culture did. Figurines of goddesses, the prevalence of female icons, and matrilocal practices—such as evidence that men may have moved into the homes of their wives—suggest a possible female-positive social structure.

Gurholt (2004) notes that although the Indus Valley civilization was likely patriarchal in basic structure, it appears to have differed significantly from the more rigid patriarchy introduced by the Indo-Aryan migrants. She associates the rise of patrilineality, patrilocality, and pronounced social hierarchy with the Aryan incursion and the institutionalization of Brahmanism. “The Indo-European Aryans,” she writes, “contributed to and heightened the hierarchical, patriarchal social structure of ancient India.” She also contends that sexism and patriarchy were inconsistent with the earliest Vedic and Buddhist philosophical principles, which emphasized spiritual equality and individual realization.

During the early Vedic period (c. 1500–1000 BCE), women appear to have enjoyed a degree of agency and social participation that would later decline under classical Brahmanical orthodoxy. Vedic texts refer to women participating in religious rituals, tribal assemblies, and receiving formal education. They were permitted to choose their husbands, marry more than once, remarry as widows, and even divorce. Child marriage was unknown in this period. Some women also pursued asceticism and spiritual realization, including the path of renunciation.

Despite being composed primarily by and for men, the Vedas themselves include hymns attributed to female sages, such as Lopamudra, Apala, Ghosha, Vagambhrini, and Visvavara in the Rigveda. The Samaveda and later texts also mention additional female seers. In the Upanishads and epic literature, women like Maitreyi, Gargi, and Sulabha are portrayed as intellectually and spiritually accomplished figures who engage in philosophical discourse with men on equal terms.

These examples suggest that women were not only participants in ancient Indian religious and philosophical life, but in some cases were regarded as authorities. However, over time, as Brahmanical patriarchy solidified, many of these rights and freedoms were curtailed.

Later Vedic Period (1000 BCE–500 BCE)

During the later Vedic period, the increasing dominance of Brahmanism coincided with the consolidation of patriarchal norms that profoundly restricted the social, religious, and intellectual roles of women. A shift occurred from the earlier ritual use of Soma—possibly a psychoactive plant used in Vedic rites—to a symbolic fire sacrifice, accompanied by an increasing formalization and priestly control of religious practice. Over time, the exact identity and preparation of Soma was forgotten, and its ritual significance became largely symbolic.

Parallel to this, the reverence for female divinities diminished. Goddesses lost prominence within the Vedic pantheon, and women were increasingly excluded from religious life. Rights that Vedic women once appear to have enjoyed—such as access to education, participation in tribal assemblies, freedom in marriage, and spiritual autonomy—were gradually withdrawn. Vedic study was increasingly restricted to male Brahmans, and women were barred from both ritual authority and intellectual inquiry.

Social customs hardened accordingly. Arranged marriages and child marriages became more common. Widow remarriage was discouraged or prohibited; property rights were denied to women; and divorce, once allowed, was outlawed. Female chastity was sacralized and rigidly enforced, not only for spiritual reasons but also as a mechanism of social control. Women were seen as embodiments of family honour and became subject to increasingly restrictive codes of behaviour, including seclusion, veiling, and the idealization of self-immolation as a supreme act of loyalty. In legal and ritual texts like the Manusmriti, women were often likened to the lowest social class, emphasizing their subservience.

These developments paralleled a deeper ideological shift within Vedic religion. A growing division emerged between two classes of deities: the divine beings and the antigods. While earlier hymns of the Rigveda often depict them as spiritually powerful and even noble beings—such as Varuṇa, Mitra, and Aryaman—later texts began to vilify the antigods as demonic and cast them as enemies of the divine beings. This theological inversion appears to reflect a socio-political realignment within Vedic society, whereby older, possibly non-Brahmanical or heterodox traditions were suppressed by a more hierarchical, Brahman-dominated orthodoxy.

In western parts of the Indian subcontinent and Iran, these rejected traditions may have retained their influence. The Zoroastrian religion, which arose in ancient Persia, reveres Ahura Mazda—“Wise Lord”—whose name and nature bear striking resemblance to the Vedic antigod Varuṇa. In Zoroastrianism, daevas are malevolent beings, suggesting that the division between divine being and antigod may reflect not merely mythology but also an historical schism between different Indo-Iranian religious cultures. In this view, the triumph of deva worship in India correlates with the institutionalization of caste, patriarchy, and Brahmanical supremacy.

Developments in 6th–5th Century BCE India

By the time of the Buddha in the 6th to 5th centuries BCE, the traditional Brahmanical culture rooted in Vedic ritualism had become increasingly rigid and disconnected from the socio-economic realities of early Iron Age India. The sacrificial religion of the Brahmans, developed for an earlier tribal and agrarian context, no longer spoke meaningfully to the urbanizing populations of the Middle Gangetic Plain. This region—once part of the heartland of the Indus Valley civilization some two millennia earlier—had become a crucible of intellectual and spiritual experimentation. New forms of wealth were emerging through trade, artisanal production, and land ownership, elevating the status of merchant and working classes. The resulting social mobility unsettled traditional caste hierarchies and fostered widespread questioning of inherited authority—both political and religious.

This ferment produced a variety of new religious movements and philosophical schools, among them the Śramaṇa traditions, which included Buddhism, Jainism, and Ajivikism. The more mystical teachings of the Upaniṣads were also gaining traction, challenging the ritual orthodoxy of the Brahman elite with introspective and experiential approaches to liberation. Criticism of Brahmanical privilege and the authority of the Vedas became increasingly common.

The political landscape was equally dynamic. The Indian subcontinent at this time was divided into sixteen great states, ranging from Gandhāra and Kamboja in the northwest to Magadha and Anga in the east. These polities included hereditary monarchies, oligarchies, and even quasi-republics such as the Licchavis and the Buddha’s own Śākya clan. Political instability was common, marked by wars of succession, assassinations, and inter-state conflict. The Buddha himself lived to see the destruction of his homeland by King Viḍūḍabha of Kosala, a traumatic event remembered in the Pāli Canon.

Life for many was precarious. The rise of centralized kingdoms brought increased taxation and state control, often falling hardest on small farmers and the rural poor. Brigandage and lawlessness plagued the roads and forests. Yet alongside this insecurity, economic life was thriving. Artisan guilds flourished, labor became increasingly specialized, and urban centres such as Vārāṇasī and Rājagaha grew in importance. The emergence of a wealthy mercantile class disrupted traditional social structures and eroded the ideological monopoly of the Brahmans.

Women’s status, particularly that of widows, was often dire. Legal and social constraints severely limited their autonomy. Denied the right to inherit property or remarry, many women were forced into prostitution as a means of survival. It is in this context that the early Buddhist community’s relative tolerance of prostitution may be understood—not as approval, but as a pragmatic accommodation to social realities rejected by orthodox Brahmanism.

This period corresponds to what the German philosopher Karl Jaspers termed the Axial Age, spanning from roughly 800 to 200 BCE—a time when parallel revolutions in thought arose independently across several ancient civilizations, including Confucianism and Taoism in China, Greek philosophy, Hebrew monotheism, and the Iranian teachings of Zoroaster. The historian of philosophy Eric Voegelin referred to it as the Great Leap of Being—a shift toward reflective consciousness and transcendental ethics.

Interestingly, the midpoint of the Axial Age (circa 500 BCE) falls almost exactly between the mythical start of the Kali Yuga (3102 BCE) and the projected future culmination of the current age. The idea of historical cycles recurs in Indian thought, and some esoteric traditions have linked the 21st century to the dawn of a new spiritual epoch. The Kalachakra Tantra, for example, predicts the full manifestation of Shambhala in the year 2424 CE, which some interpret as a kind of second Axial turning.

Modern futurists have offered secular parallels. Ray Kurzweil has proposed the year 2045 as the date of the Technological Singularity—a predicted moment when artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence by a factor of one billion, triggering an unpredictable transformation of civilization (Kurzweil posits 2029 as the date when machine intelligence will equal human intelligence). Intriguingly, this lies not far from the end of the Mayan Long Count in 2012 CE, whose starting point (3114 BCE) is within a decade of the traditional Indian date for the beginning of the Kali Yuga. Such resonances—though speculative—suggest that both ancient and modern thinkers have sensed a deep structure in time, marked by periodic inflection points.

The Buddha, situated near the centre of the first Axial Age, appears as a paradigmatic figure of spiritual transformation. Likewise, the 8th-century tantric master Padmasambhava, credited with transmitting Vajrayāna Buddhism to Tibet, may be seen as a midpoint between the Buddha’s time and our own, standing at the hinge of two epochs in the unfolding Buddhist vision of time.

The View of Women in the Shakti, Samana, and Shaivite Countercultures

Shaktism

A famous motif found on a seal excavated at Mohenjo-Daro, one of the principal sites of the Indus Valley Civilization, depicts a horned figure seated in a cross-legged posture and surrounded by animals. This figure has been tentatively identified by some scholars as a proto-form of Shiva in his aspect as Pashupati, “Lord of Animals.” The interpretation is speculative but compelling, especially in light of parallels with later Hindu iconography. Similarly, certain phallic objects discovered at Harappan sites have been interpreted by some as precursors of the Shivalingam, though this too remains controversial among archaeologists.

The broader significance of these finds lies in the possible evidence for early fertility cults or symbolic systems that later evolved into Śaiva and Śākta traditions. In classical Shaivism, Shiva represents the eternal masculine principle—creative, ascetic, and ultimately transcendent. Yet, in this tradition, Shiva is said to be inert without Shakti, his consort and the personification of divine energy (śakti meaning “power” or “force”). Shakti embodies the dynamic, creative, and transformative aspect of the cosmos. In the human sphere, she is also associated with intelligence, compassion, and the spiritual force that drives liberation.

Even if the identification of the horned Indus figure with Shiva remains unproven, the goddess principle is well-attested in Vedic literature. Various goddesses such as Aditi, Uṣas, Prithvi, and Sarasvati appear throughout the Rigveda, often embodying cosmic and moral order, fertility, and wisdom. While the systematic theology of Shaktism emerged more fully by the Gupta period (circa 400 CE), its roots can be traced to earlier Vedic and pre-Vedic expressions of divine femininity. How far back this extends is still unknown, though some scholars suggest connections with prehistoric fertility cults attested in Paleolithic and Neolithic artifacts.

S(h)amanism

By the 5th and 6th centuries BCE, the established Vedic Brahman orthodoxy was increasingly unable to meet the spiritual and existential needs of many in Indian society. A widespread sense of disillusionment, intellectual ferment, and moral questioning had taken hold. In response, a variety of new religious and philosophical movements arose, competing for followers and legitimacy. These movements included materialist, hedonist, deterministic, and agnostic schools of thought, alongside evolving forms of Upanishadic Brahmanism and a growing community of religious renunciants.

By the time of the Buddha, this counterculture—a loosely affiliated milieu of wandering ascetics, seekers, and philosophers—was already well established, especially in the northeastern regions of the subcontinent, where Brahmanical influence was relatively weak. When Siddhattha Gotama renounced the household life at the age of 29, he joined this world of seekers, shaving his head and donning the ochre robe. This act marked his entrance into a spiritual landscape not yet defined by formal monastic institutions, but rather by itinerant practice and personal discipline.

The Pali word samana, from Sanskrit śramaṇa, refers to a renunciant or spiritual striver—literally “one who exerts.” It derives from the root √śram, meaning to labor, strive, or become weary, especially in a religious context. While it is not etymologically related to the Tungusic word shaman, both denote individuals engaged in altered states and spiritual disciplines. The Sanskrit prefix sam- (as in samādhi) means “together” or “complete” and is unrelated to śramaṇa. Nonetheless, Buddhist texts do portray spiritual practice with vivid imagery of heat, fire, and light—echoing ideas of inner transformation and the development of psychic powers, which align symbolically with the strenuous exertions of an ascetic on the path to awakening.

The ascetic counterculture rejected the authority of Brahmanism and the Vedas, although many of the spiritual and religious concepts of the ascetics were also prefigured in the Upanishads. It is important to note that the ascetic movement specifically rejected the authority of both the Brahman caste and the Vedic textual traditions, despite these similarities. Thus, the philosophy of the Buddha must be decisively distinguished from the so-called orthodox schools, which accepted Vedic authority. The latter became the well-known Samkhya, Yoga, and Vedanta philosophical schools of orthodox Hinduism, amongst others. This is a key point to remember in the context of the late Vedic attitude toward and treatment of women.

The ascetics set out to discover the truth for themselves experientially. To this end, they adopted three fundamental practices: austerity, to purify karma; meditation, to cultivate mental concentration; and ‘view’ or philosophy, to cultivate wisdom or understanding – the same threefold division we find in the Pali Canon. Jainism likely predates the Buddha, though in what form is debated. According to Jain tradition, the 23rd Tirthankara, Parshva, lived around the 8th century BCE, placing the tradition’s roots at least a century or two before the Buddha’s time. However, Jainism as it is known today was largely shaped by Mahavira, a contemporary of the Buddha. Some scholars have speculated that Jainism preserves elements of non-Vedic or pre-Aryan religious culture, possibly even remnants of the Indus Valley Civilization, though this is contested and remains unproven. While Jainism and Buddhism share many features—such as renunciation, moral causality, rebirth, and liberation—the Buddha explicitly criticized Mahavira’s teachings, especially extreme asceticism and belief in an eternal soul, and distinguished his own path as a Middle Way. After his renunciation, the Buddha sought out two leading meditation teachers of his time: Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta. Under Āḷāra, he mastered the attainment of the sphere of Nothingness, and under Uddaka, who represented the teachings of the sage Rāma, he attained the even subtler state of Neither-perception-nor-non-perception. Although both teachers recognized his mastery, the Bodhisattva concluded that these attainments, while profound, did not lead to full liberation. There is no evidence that either teacher was affiliated with Sāṃkhya or Jain traditions; their teachings appear to reflect early meditative systems preceding formal Buddhist doctrine. Finally, the Buddha fell in with the Group of Five, led by Kondanna, the Brahman ascetic who had predicted at his birth that Gotama would become a World Teacher. The group of five had renounced the worldly life about the same time as the Buddha and practised extreme austerities, including mortification of the body, breath-control, mind-control, and extreme fasting, practising in cemeteries and elsewhere, similar to the Shaivites (see below). After failing to find what he sought with Kalama and Ramaputta, Gotama joined them in these practices, until he was on the verge of dying. The Buddha’s practice of these austerities is vividly described in the Pali Canon. About the age of 35, on the very verge of death, Gotama accepted some milk-rice from a passing village girl, Sujata, at which point the Group of Five abandoned him as having reverted to the effeminate life of his youth. Gotama was on his own and had still not found what he sought.

Shaivism

Shaivism, one of the major currents of Indian religious tradition, can be traced in part to the Śvetāśvatara Upanishad, composed circa 400 BCE. This Upanishad is the earliest known text to present Rudra—a Vedic deity later identified with Shiva—as a supreme personal god. Although the Śvetāśvatara Upanishad does not represent fully developed Shaivism, it forms a crucial textual foundation for its later evolution. The historical Buddha’s passing is dated around 400 BCE, roughly aligning with the era of this Upanishad, though both dates are subject to scholarly debate.

The origins of Shaivism, however, are significantly older and more complex. Its roots lie in a broad spectrum of ascetic, yogic, and possibly pre-Vedic (or non-Vedic) cultic traditions, which were later assimilated into Brahmanical frameworks. Some scholars suggest links to the Pashupati figure of the Indus Valley Civilization—depicted on a famous seal in a meditative posture surrounded by animals—though this remains speculative and controversial.

Certain Shaivite traditions, particularly the more radical ascetic sects, practiced extreme austerities, cremation ground rituals, the use of human bones in worship, and the rejection of caste norms. These practices were not universal across all Shaiva lineages but were characteristic of sects such as the Kapalikas and later Aghoris. Elements such as yoga, celibacy, reverence for the feminine principle (Shakti), and renunciation of household life were shared among various renunciate movements in ancient India, including Jainism and early Buddhism.

During his renunciant period, prior to awakening, Gotama Buddha undertook severe austerities, including prolonged fasting, breath control, and absorption in the formless meditative attainments. He also practised cemetery-dwelling, sleeping on beds made of human bones and using a skeleton as a seat, according to early sources such as the Paṭisambhidāmagga. In the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta and other discourses, he explicitly advocated charnel ground meditation, including contemplation of corpses in various stages of decomposition, as a method for transcending attachment to the body and overcoming fear of death. These practices, far from peripheral, formed part of a disciplined spiritual confrontation with impermanence and revulsion, foundational to early Buddhist training. This austere and uncompromising path closely parallels certain Shaivite and proto-Tantric disciplines, which also embraced cremation ground ritual, confrontation with death, and the transgression of orthodox caste and purity codes.

In his teachings, the Buddha challenged the authority of the Brahman caste, opened the order to women, and welcomed those of all social classes. His dharma reflects a return to a primordial spiritual ethos, unmediated by Vedic ritualism and caste exclusivity. He portrayed his teaching as timeless and ancient, yet distinct from both the Brahmanical orthodoxy and the heterodox doctrines of his contemporaries.

In the Angulimāla Sutta, the Buddha converts a violent outlaw whose spiritual background remains ambiguous. Scholar Richard Gombrich has speculated that Angulimāla may have been associated with a fringe ascetic or cremation-ground cult, perhaps akin to early Śaiva or proto-Tantric groups. If so, the Buddha’s personal acceptance of Angulimāla as a disciple can be seen as an emblematic act of spiritual inclusion, transformative redemption, and doctrinal contrast.

Evaluating the Buddha’s View Toward and Treatment of Women

The Sex Life of the Buddha

Unlike Jesus, generally portrayed in Christian canonical sources as celibate and ascetic, the Buddha is depicted in Indian Buddhist literature as embodying an ideal of robust masculinity. John Powers, in his book A Bull of a Man: Images of Masculinity, Sex, and the Body in Indian Buddhism, explores this portrayal, highlighting how the Buddha’s physical and virile attributes align with Indian ideals of a “great man.”

According to traditional accounts, at his birth, the Buddha exhibited the 32 major physical characteristics of a great man, including long, slender fingers; smooth, golden-colored skin; a well-proportioned body; even white teeth; a strong jaw; long eyelashes; deep blue eyes; a prominent cranium; and a deep, resonant voice . These features signified his potential to become either a universal monarch or a fully enlightened Buddha.

Raised in luxury by his father, Suddhodana, who hoped his son would succeed him as leader of the Shakyan clan, Siddhartha (Gotama) was provided with every sensual pleasure. He married Yasodhara at 16 and had a son, Rahula, by the age of 29. The Magandiya Sutta (MN 75) records the Buddha reflecting on his past indulgence in sensual pleasures:

Magandiya, formerly when I lived the home life, I enjoyed myself, provided and endowed with the five cords of sensual pleasure: with forms cognizable by the eye… sounds cognizable by the ear… odours cognizable by the nose… flavors cognizable by the tongue… tangibles cognizable by the body that are wished for, desired, agreeable, and likable, connected with sensual desire and provocative of lust.

This acknowledgment underscores that the Buddha’s renunciation was not born from ignorance of worldly pleasures but from a profound understanding of their transient nature. His departure from palace life marked a deliberate shift from sensual indulgence to spiritual pursuit, embodying the transition from worldly attachment to enlightened detachment.

Negative Views of Women in the Pali Canon

The Pali Canon contains numerous passages that reflect deeply negative and misogynistic attitudes toward women, consistent with the patriarchal social context of ancient India. For example, some texts assert that a woman is incapable of attaining Buddhahood, presenting female birth as karmically inferior due to five specific types of suffering to which women alone are subject: separation from family, menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, and subordination to men.

The Vinaya and sutta literature describe a hierarchical relationship in which a wife is expected to obey her husband unquestioningly, even to the point of self-sacrifice. Similarly, the female monastic is institutionally subordinate to the male monastic, regardless of seniority or spiritual attainment.

Sexual activity is portrayed in starkly negative terms. The Buddha is reported to have described sexual intercourse as the “opposite of the Dhamma,” something impure and to be conducted in secret. Some Vinaya texts contain hyperbolic warnings against sexual misconduct, including metaphors suggesting that sexual union with a woman is worse than contact with venomous snakes or burning coals—expressions designed to emphasize renunciation rather than literal prescriptions.

Regarding women’s capacity to arouse desire, the texts often depict the female form as a powerful temptation and liken women to “sharks” or “snares of Māra” (the personification of delusion and temptation). The Anguttara Nikaya records the Buddha cautioning monks to avoid women altogether, even dead ones, to prevent lust and spiritual distraction.

Women are further described as possessing negative qualities such as envy, miserliness, sensuality, and secretiveness, which purportedly limit their ability to participate in leadership, commerce, or travel alone. These descriptions reflect social prejudices rather than spiritual truths, as evidenced by the Buddha’s contradictory actions in admitting women to the monastic order and teaching them the path to liberation.

The Buddha’s own attitude toward women is complex and at times contradictory. While he acknowledges the challenges posed by sensual desire and social roles, he also provides a radical platform for female spiritual attainment—albeit within a framework still shaped by the patriarchal norms of his time.

These texts must be understood in their historical and cultural context, recognizing both the limitations of ancient Indian society and the Buddha’s often progressive challenges to social convention. The Pali Canon’s sometimes harsh language about women reflects not only spiritual concerns about desire and attachment but also the social realities of a deeply gendered culture.

According to the Pali Canon, the original order of the Buddha was an order of men only. After the death of his father, Suddhodana, about seven or eight years following the Buddha’s enlightenment and the establishment of the order (perhaps ca. 440 BCE) the Buddha’s aunt and foster-mother, Maha Pajapti Gotami, resolves to be ordained, along with 500 women of the court. She approaches the Buddha when he is visiting Kapilavastu, for permission to join the order, but he refuses her request. Distraught, the women shave their heads and put on robes anyway, and follow the Buddha to Vesali, a distance of about 300 kms (186 miles). This must have taken them about a month. Distraught and physically exhausted, she approaches Ananda, who is portrayed in the discourses as quite sympathetic to women in general, to intercede with the Buddha. Ananda approaches the Buddha on her behalf. Once again, the Buddha refuses. Ananda’s subsequent discussion with the Buddha is quite famous. He asks the Buddha whether, therefore, women are capable of attainment. The Buddha admits that they are capable of attaining arhantship, the same as men. The self-contradiction in the Buddha’s position thus exposed, the Buddha finally relents, acceding to Ananda’s request, but he declares that because of the ordination of women the longevity of the order will be halved, from one thousand to only five hundred years. Moreover, he imposes eight special rules on the female monastic order that\ permanently subordinates them to the male monastic order. These are called the eight Garudhammas (‘heavy rules’), viz.:

1) A nun who has been ordained even for a hundred years must greet respectfully, rise up from her seat, salute with joined palms, and do proper homage to a monk ordained but that day.

2) A nun must not spend the rains in a residence where there are no monks.

3) Every half month a nun should desire two things from the Order of Monks: the asking as to the date of the Observance day, and the coming for the exhortation. After the three-month rainy season retreat a nun must ‘formally invite admonition’ before both orders in respect of three matters, namely what was seen, what was heard, what was suspected.

5) A nun, offending against an important rule, must undergo discipline or penance for half a month before both orders.

6) When, as a probationer, she has trained in the six rules for two years, she should seek higher ordination from both orders.

7) A monk must not be abused or reviled in any way by a nun.

8) Admonition of monks by nuns is forbidden.

Over the course of time, these eight additional rules expanded to 311 rules for nuns, compared to 227 for monks. According to another computation, there are 110 extra rules for nuns. After a thousand years, the female monastic order died out in India and most other places. In Thailand, which follows the conservative Theravada tradition inherited from Sri Lanka, it is literally illegal for a woman to “impersonate” a monastic by putting on robes.

There are many rules in the Buddhist Vinaya, the monastic rules applicable to monks, concerning women and nuns. A monk may not have sexual intercourse or lustful bodily contact with a woman, nor may he make lustful remarks to a woman, including asking her for sexual favours. He may not arrange for a date, affair, or marriage with a woman on behalf of another person. An unrelated nun may not wash a monk’s robes or give him robes as a gift. A nun may not wash, dye, or card raw wool for a monk. A monk may not lie down in the same building as a woman. He may not teach a woman more than five or six verses, unless another knowledgeable man is present. He may not exhort the nuns in the nuns’ quarters unless she is ill. He may not exhort the nuns for worldly gain in any case. He may not give an unrelated nun cloth for a robe, or sew it or have it sewn, unless it is given in exchange. A monk may not travel on the road with a nun, even between villages, unless it is by caravan and the road is unsafe, or travel with a nun by boat in any direction upstream or downstream other than directly crossing a river. He may not travel on a road with a woman in any case. He may not eat alms food obtained by the prompting of a nun. He may not sit alone with a nun. He may not accept food from an unrelated nun. The punishment for violating any of these rules ranges from expulsion from the order to verbal acknowledgement, depending on the severity of the offence.

Positive Views of Women in the Pali Canon

Despite the views summarized above, the Buddha also expresses many positive views concerning women in various places. Women figure prominently in both the discourses and the post-canonical commentaries (see Hellmuth Hecker, “Great Women Disciples of the Buddha,” chapter 7 of Nyanaponika and Hecker, 1997). I have already mentioned the Buddha’s acknowledgement that women are capable of attaining emancipation. This is elaborated at great length in other discourses, where the Buddha goes to some length to describe all of the levels of attainment from faith follower to arhant, and emphasizes that many members of the order, including both men and women, have attained all of the various stages of spiritual development. Indeed, the Buddha implies that women must exist at all levels of spiritual development for the order to be complete. The Buddha criticizes the Brahman practice of arranged marriage and defends the right of women to marry freely for love. He explicitly identifies women’s rights as the fifth principle of a healthy and stable society, referring specifically to the Vajjians. When the married Bhagga householders Nakulapita and Nakulmata approach the Buddha and declare their love for each other, asking him whether they can ensure that they would be reborn together, rather than criticize them the Buddha praises the couple and declares that they can be reborn together as divine beings, a destination reserved for the most pious, if they observe the same faith, morality, generosity, and wisdom. The evidence of the Pali Canon, especially the Songs of the Wise Women (Therigatha), clearly shows that the early order included many women, both monastic and lay, many of whom were highly esteemed and spiritually advanced practitioners, even arhants, just as was the case during the early Vedic period. Some great women disciples of the Buddha included Visakha, the Buddha’s chief patroness; Mallika; Khema of great wisdom; Bhadda Kundalakesa, the debating ascetic; Kisagotami; Sona; Nanda, the Buddha’s half-sister; Queen Samavati, the embodiment of loving kindness; Patacara, preserver of the Vinaya; Ambapali, the generous courtesan; Sirima; Uttara; and Isidasi. This is perhaps the best evidence of all for the view that the Buddha made no distinction between women and men.

Analysis

In the introduction to his translation of the Numerical Discourses of the Buddha (Anguttara Nikaya), Bhikhu Bodhi acknowledges that the positive and negative statements concerning women found throughout the Pali Canon are mutually self-contradictory. It is impossible to believe that the Buddha held all these views simultaneously. Bodhi also doubts the historicity of the famous dialogue in which Ananda convinces the Buddha to admit women to the order, citing “anachronisms hard to reconcile with other chronological information in the canon and commentaries.” Scholars also doubt the antiquity of the eight special rules, one of which refers to probationary nuns, a category that did not exist when Mahapajapati was ordained. Consequently, it cannot be original. There is also reason to disbelieve the account of the admission of Mahapajapati to the order, since the Exposition of Offerings (Dakkhinavibhangha Sutta) in the Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha (Majjhima Nikaya) presents the female monastic order as already existing when Mahapajapati goes for refuge to the Buddha, the Teaching, and the Order, without any suggestion that the Buddha opposed her admission. It appears, then, that this whole complex was invented to justify the eight heavy rules.

In defence of the Buddha’s purported reluctance to ordain women, apologists have cited possible concerns about social prejudice, including the Buddha’s realization that the order could not survive without popular support, and the safety of the nuns, who would be subjected not only to social scorn and even abuse, but also by the ravages of the environment at a time when the order had not yet established itself with parks and monasteries. By accepting women into the order, the Buddha was setting himself against the entire late Vedic tradition of the deva worshippers that was now universally accepted by the society of his time. It was unheard of for women to leave the household life and follow the path of ascetic, much as it was in Hindu India until very recently. Although he was criticized for breaking up the family unit, and the order was not welcomed everywhere, it is a testament to the Buddha’s charisma and the respect in which he was held that there is not more indication of dissension in the Pali Canon than there is.

Thus, the Pali Canon itself forces us to make a judgement. Either we accept that the Buddha reluctantly admitted women to the order on what amounts to a technicality, but instituted rules to curtail and limit the damage resulting from this concession, or we take the view that the misogynistic passages are later additions that reflect the social prejudices of ancient India, especially male monastics, that we have seen began to supplant the older, more tolerant view of women during the late Vedic period. The latter view is consistent with the Buddha’s declaration that he considered the Brahmanism of his time to be a degenerate remnant of a primordial tradition that he sought to restore. With respect to the latter, it is interesting to note that the Buddha clearly opposed the caste system, arranged marriage, and authoritarianism, all things that appeared during the late Vedic period with the rise of the newer deva worshippers who cast down the antigods to the foot of Mount Meru. Psychologically, this sounds like a massive act of self-inflicted psychosocial repression. This makes one wonder if the older tradition to which the Buddha alludes was in fact that of the older system of asura worship, which actually means “powerful spiritual being,” with which he was in secret sympathy, which also, like the Buddha, opposed the Vedas and deva worship, i.e., Aryanism, despite the reversal of terms that clearly predominates in the Pali Canon itself.

The View of Women in the Early Buddhist Councils

The First Buddhist Council

The First Buddhist Council was convened in the year following the Buddha’s passing about 400 BCE according to modern scholarship by King Ajatashatru, the king of Magadha in Rajgir, the capital, according to tradition. Although in his final instructions the Buddha had said that the order should have no leader after him, but should be led by the teaching alone, Mahakassapa, the Buddha’s foremost disciple in ascetic practices, assumed the leadership of the order after the Buddha’s death, and convened the First Buddhist Council in response to suggestions by the monk Subhadda that with the Buddha’s death the Vinaya rules of the order might be relaxed. Although this is presented in the Theravadin literature as a criticism, in fact according to the Great Final Emancipation (Mahanibbana Sutta), the Buddha had indicated that after his death the lesser and minor rules of the Vinaya might be abolished. Thus, Mahakassapa convened 500 arhants to consolidate the tradition of the teaching, including Ananda, who conveniently attained arhantship during the night before the council began to meet from July to the following January. Upali, the foremost disciple in keeping the precepts, began by reciting the rules of the Vinaya in their entirety, especially the rules that entail mandatory and automatic expulsion from the order – i.e., sex, stealing, killing, and lying about one’s spiritual status. Ananda then recited the discourses.

Ananda had a tough time of it, however. He was criticized, presumably by Mahakassapa, for “convincing” the Buddha to ordain women. Many male arhants were extremely opposed to this, despite the clear fact that the Buddha had approved it. There was also the question of the minor and lesser rules of the Vinaya that the Buddha had said in his final instructions to Ananda might be abolished. Since it had not occurred to Ananda to ask the Buddha which rules he was referring to, the conservative Council decided to keep them all. The Council also decided to allow the ordination of women, subject to the eight heavy rules and expanded the rules to include additional rules for female monastics, despite the fact that the Buddha had also declared that no new rules were to be made. It seems likely that the eight heavy rules were codified at this time, perhaps as a compromise between two competing factions.

The foregoing account creates serious “theological” issues for the Theravada in particular since all of the members of the First Buddhist Council are regarded as arhants. This problem came to a head a hundred years later during the Second Buddhist Council, during which the fallibility and imperfection of arhants became a cause of disagreement between two nascent Buddhist schools, the Mahasamghikas, who took the view that arhants are fallible, and the Sthaviras, who took the view that arhants are infallible. These differences were summarized in the Five Points of Mahadeva. The Mahasamghikas represented the majority consensus, and subsequently developed into the Mahayana, whereas the minority dissidents, the Sthaviras, subsequently developed into the Theravada. With respect to the present topic, it is clear that the First Buddhist Council endorsed a view of women and nuns that is fundamentally misogynistic, and the Pali Canon, which is the record of Buddhist teachings accepted by the Theravada, is explicitly so. As I have also shown, the First Buddhist Council overruled the Buddha’s own injunctions to not appoint a leader and not to abolish the lesser and minor rules, and subsequent councils clearly also added rules and in particular rules designed to subordinate the nuns to the monks. That the attainments of arhantship and Buddhahood are different also seems to be supported by the canonical assertion, if we accept it, that women can become arhants but not Buddhas. The ten powers of an arhant also differ significantly from the ten powers of a Buddha according to the Pali texts. On the other hand, if we accept the Theravada view that arhants are infallible, then we must accept Buddhist misogyny as a view. If we are not willing to accept the inferiority of women, we cannot in good conscience accept the lineage derived from the minority Sthavira position. Therefore, we cannot accept Theravada as the final summation of the teaching. Since the Buddha indicated that in the absence of consensus we must accept majority rule, we are compelled to the alternative view as the correct Buddhist view.

The View of Women in Buddhism Today

After the Buddha’s death about 400 BCE, Indian society continued to oppress women. Beginning in the fifth century CE, by the 11th century the practice of widow-burning became the model of how a pious wife should respond to the death of her husband. The Muslim incursion into India (12th–16th centuries), which virtually wiped Buddhism out in India, including the female monastic order, followed by the British conquest of India, beginning in the 17th century, further intensified the already deeply-rooted Indian misogyny. Meanwhile, the female monastic order had virtually disappeared from India and Sri Lanka by the 11th century. Widely disparaged in Buddhist countries, and discriminated against where it did exist, the female monastic order only survived continuously in Eastern (Chinese) Buddhism, ironically in view of Confucian ideas of the subordination of women. Today efforts are underway in several countries to restore the female monastic order, albeit based on the old model; the Dalai Lama has made similar efforts in northeast India. As a result, there are a few tens of thousands of fully ordained Buddhist nuns in the world today.

Socially, Buddhist women have fared better than Indian women, however. In general, Buddhist societies respect single women, including spinsters, divorced women, and widows. Laws concerning divorce and the division of property and children are fairly equal between husband and wife. Outside China, where Confucian notions predominate, women are fairly free, including in business, trade, and agriculture. In Eastern Buddhism, Zen/Ch’an Buddhism emphasizes sexual equality. Women may also be found exercising the professions of law and medicine, and have been politically influential. Many Buddhist women enjoy sexual freedom, property rights, and self-determination. Women may also be influential in religious institutions. Mahayana tends to view men and women as equal whereas Theravada still sees the Bodhisattva path as suited only for rare and heroic men. Female spiritual figures are most widespread in Vajrayana (Buddhist Tantra).

Conclusion

Indian culture differs from the other great originating cultures of humanity in that most cultures began with the patriarchal suppression of women, followed by their progressive emancipation, whereas Indian civilization began with women holding a position of unique power and privilege, followed by their progressive suppression commencing about 1100 BCE. This “transvaluation of all values” appears to have coincided with a social schism in which an original cult of asura worship, great cosmological abstractions associated with the powers of nature, was displaced by a new, aggressive cult of deva worship based on notions of patriarchal authority, conformity, Brahmanic dominance, caste, and misogyny derived from the Aryan incursion. By the time of the Buddha, Vedic society was breaking down and a counterculture of wandering “shamans,” suggestive of the later Shakti and Shaiva cults that eventually developed into Tantra, had emerged. After studying meditative discipline with two non-Vedic teachers in succession, the Buddha joined the ascetic counterculture and became an extreme ascetic for a number of years, almost dying in the process, followed by his enlightenment experience. It is noteworthy that both the Shakti and Shaivite cults were not misogynistic in their attitudes to femaleness.

The conflicting attitudes toward men and women in Indian society appear in the Pali Canon in the conflicting attitudes to women attributed to the Buddha. However, it appears that the Buddha did not make a fundamental distinction between men and women, asserting that both men and women are equally capable of attainment, and freely teaching women and admitting them to the order on an equal basis, rather like Jesus, the founder of Christianity, for which the latter was also severely criticized by the Jewish establishment in Jerusalem. If the Buddha made a distinction between the orders of monks and nuns, it was to protect the nuns and appease social prejudice. This unpopularly tolerant attitude appears to have created a great deal of consternation amongst the more conservative male followers of the Buddha, but they seem to have largely avoided criticism out of respect for the Buddha. This changed after the Buddha’s death, when a major rift seems to have occurred during the First Buddhist Council, when the male monastics criticized Ananda for supporting the ordination of women. That they were not the only side of this debate is suggested by the fact that a compromise appears to have been reached in which the order of nuns was subordinated to the order of monks but allowed to exist. Otherwise, it seems likely that the nuns would have been suppressed altogether. The pious forgeries concerning Mahapajapati, Ananda’s subsequent debate with the Buddha, and the eight heavy rules were created to explain the final decision of the First Buddhist Council, which led ultimately to the disappearance of the female monastic order. Moreover, the addition of numerous special rules for female monastics, all with the purpose of subordinating the nuns to the monks, clearly violates the Buddha’s instructions not to add extra rules to the Vinaya. Over the following three centuries numerous misogynistic passages were introduced into the discourses, while the more favourable statements of the Buddha concerning women were also allowed to stand because they were too well established to be refuted, thus creating the somewhat bizarre self-contradictions that we find in the Pali texts today. Likely, over the course of 300 years there were diverse currents and sub-currents of thought amongst the anonymous redactors of the Pali Canon itself, of which we know little or nothing. Meanwhile, Indian society continued in its misogynistic course, exacerbated by Muslim and British colonial influences. Thus, in contemporary Nepal, for example, we find a significantly more liberal society than India proper, since Nepal was never subjugated to Muslim or British rule. Buddhism itself split into two large movements, one aligned with the dominant conservative social attitude and one aligned with the more liberal attitude that, it appears, was actually advocated by the Buddha. Fortunately, for those of us who do not believe in the inferiority of women, the latter has become the majority view in the Buddhist world today.

Revised June 15, 2025

Bibliography

Ancient Wisdom Foundation (accessed 2014, May 19). “Mohenjo-Daro.” http://www.ancient-wisdom.co.uk/Pakistanmohenjo.htm.

The Aryan Invasion (2011, April 17). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eyZRhG5QQK4.

Berzin, Alexander (2007, April). “Indian Society and Thought before and at the Time of the Buddha.” http://www.berzinarchives.com/web/en/archives/study/history_buddhism/buddhism_india/indian_society_thought_time_buddha_.html.

Bodhi, Bhikkhu, trans. (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. The Teachings of the Buddha. Vol. 2. Boston: Wisdom.

———-, trans. (2012). The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Anguttara Nikaya. The Teachings of the Buddha. Boston: Wisdom.

Chandra, Dilip (2013, April 4). “Vedic Civilization.” http://dilipchandra12.hubpages.com/hub/Vedic-Civilization.

———- (2013, Aug. 17). “Ancient Indus Valley Civilization.” http://dilipchandra12.hubpages.com/hub/Ancient-Indus-Valley-Civilization.

Dhamma Encyclopedia (2010, Aug. 31). “110 Specific Rules for Nuns.” http://www.dhammawiki.com/index.php?title=110_specific_rules_for_nuns.

Eckel, Malcolm David (2014, March 1). “India at the Time of the Buddha.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C15m-yZxm_E.

Eduljee, K.E. (accessed 2014, March 22). “Aryan Religions.” http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/aryans/religion.htm#prezoroastrianreligions.

Freeman, Colin (2015, March 2). “It was victim’s fault for getting raped and murdered, man convicted in infamous Indian bus case says.” National Post. http://news.nationalpost.com/2015/03/02/it-was-victims-fault-for-getting-raped-and-murdered-man-convicted-in-infamous-indian-bus-case-says.

Gombrich, Richard (2006). How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings. 2nd ed. London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. http://www.watflorida.org/documents/How%20Buddhism%20Began_Gombrich.pdf.

Gupta, Deep Raj (2002, Sept.-Oct.). “Harappan Civilization: An Analysis in Modern Context.” IGNCA Newsletter. Vol. 5. http://ignca.nic.in/nl002308.htm.

Gurholt, Anya (2004). “The Androgyny of Enlightenment: Questioning Women’s Status in Ancient Indian Religions.” Westminster College. McNair Scholars Program. http://people.westminstercollege.edu/staff/mjhinsdale/Research_Journal_1/anya_paper.pdf.

Harvey, Peter (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Knapp, Stephen (accessed 2013, Nov. 7). “Women in Vedic Culture.” http://www.stephen-knapp.com/women_in_vedic_culture.htm.

Lal, Vinay (accessed 2013, Nov. 9). “Indus Valley Civilzation.” http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/History/Ancient/Indus2.html.

Hirst, K. Kris (accessed 2013, Nov. 9). “Indus Civilization Timeline and Description.” http://archaeology.about.com/od/iterms/qt/indus.htm.

Kumar, Ashwani and Namita Singh (1997). “Buddha’s Approach Towards Woman Status.” Bulletin of Tibetology. http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/bot/pdf/bot_1997_01_02.pdf.

Loomba, Kiran (accessed 2013, Nov. 7). “Development from Sixth to Fourth Centuries BC.” http://sol.du.ac.in/Courses/UG/StudyMaterial/02/Part1/HS1/English/SM-2.pdf.

Morales, Frank (1998). “The Concept of Shakti: Hinduism as a Liberating Force for Women.” http://www.adishakti.org/forum/concept_of_shakti_hinduism_as_a_liberating_force_for_women_1-18-2005.htm.

Nakamura, Hajime (2000). Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts. Tokyo: Kosei. Vol. 1.

Nanamoli, Bhikkhu and Bhikkhu Bodhi, trans. (1995). The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom.

Nyanaponika and Hellmuth Hecker (1997). Great Disciples of the Buddha: Their Lives, Their Works, and Their Legacy. Ed. Bodhi. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

“Notes on the Dates of the Buddha Sakyamuni” (accessed 2013, Nov. 7). http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic138396.files/Buddha-Dates.pdf.

Powers, John (2012). A Bull of a Man: Images of Masculinity, Sex, and the Body in Indian Buddhism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rudgley, Richard (1998). “Soma.” In The Encyclopedia of Psychedelic Substances. http://huxley.net/soma/index.html.

Schumann, H.W. (1989). The Historical Buddha: The Times, Life and Teachings of the Founder of Buddhism. London: Arkana-Penguin.

“Status of Women in India: Historical Background” (accessed 2013, Nov. 7). http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/8105/10/10_chapter%202.pdf.

Ushistory.org (accessed 2013, Nov. 9). “Early Civilization in the Indus Valley.” Ancient Civilizations Online Textbook. http://www.ushistory.org/civ/8a.asp.

Veneration of Women in Vedic India (2006). http://www.hinduwisdom.info/Women_in_Hinduism.htm#Veneration of Women in Vedic India.

VisionTV (Sept. 21, 2012). In the Name of Enlightenment: Sex Scandals in Religion. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWhIivvmMnk.

Walshe, Maurice, trans. (1995). The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Digha Nikaya. The Teachings of the Buddha. Boston: Wisdom.

Watson, Traci (2013, April 29). “Surprising Discoveries from the Indus Civilization.” National Geographic. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/13/130425-indus-civilization-discoveries-harappa-archaeology-science.

Wikipedia (2013, Nov. 9). “Mahadeva (Buddhism).” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahadeva_(Buddhism).

———- (2013, Dec. 21). “Criticism of Buddhism.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criticism_of_Buddhism.

———- (2014, Jan. 29). “Botanical identity of soma-haoma.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Botanical_identity_of_soma–haoma.

———- (2014, Feb. 6). “Shramana.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shramana.

———- (2014, Feb. 27). “The eight garudhammas.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Eight_Garudhammas.

———- (2014, March 2). “Women in Hinduism.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_In_Hinduism.

———- (2014, March 4). “Women in India.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_India.

———- (2014, March 13). “Rishis.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rishi.

———- (2014, March 9). “Shaktism.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaktism.

———- (2014, March 10). “History of sex in India.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_sex_in_India.

———- (2014, March 11). “Indo-Aryan migration.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Aryan_migration.

———- (2014, April 7). “Soma.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soma.

Wilkins, W.J. (1900). “The Asuras.” Chap. 6 of Hindu Mythology, Vedic and Puranic. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/hmvp/hmvp43.htm.

Notes

- In Tibet the numbers are 253 rules for monks and 263 for nuns. The latter is merely on paper, because I do not believe a bhikkhunisangha was ever established in Tibet. Tibetans follow the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya.

- Other candidates for ingredients of Soma include honey, Amanita muscaria (fly agaric), ephedra, poppy seeds or pollen, cannabis, psilocybin (Psilocybe cubensis), a fermented alcoholic drink, Syrian rue (Peganum harmala), rhubarb, ginseng, opium, wild chicory, and even ayahuasca!

- Although the conventional Western dates of the Buddha are still given as 563 – 483 BCE, an increasing number of scholars now believe that the Buddha was born in the first half of the 5th century BCE. Hajime Nakamura (2000) puts his death as recently as 383 BCE.

- Banning Ajahn Brahm’s speech on bhikkuni ordination from the 11th United Nations Day of Vesak 2014 is merely the most recent confirmation of the misogyny of Theravada Buddhists. See “Banning Ajahn Brahm’s speech on nuns was a spectacular own-goal.” Note that restoring bhikkuni ordination does not restore gender equity between men and women, since the Buddhist formula of ordination for bhikkunis is inherently and intentionally discriminatory.

- Although most suttas are addressed to bhikkus, there are also suttas spoken by or to bhikkunis, and the Therigatha is composed entirely of verses written by early bhikkunis. The first sutta attributed to a bhikkuni is the Culavedalla Sutta (MN 44), attributed to Dhammadinna, declared by the Buddha to be the nun foremost in expounding the dharma. In this sutta, she expounds the dharma concerning personality, personality view, the Noble Eightfold Path, concentration, formations, the attainment of cessation, feeling, underlying tendencies, and counterparts. In the Dakkhinavibhanga Sutta (MN 142), his aunt, Mahapajapati Gotami, presents the Buddha with robes that she made for him herself. And in the Nadakovada Sutta (MN 146), Mahapajapati Gotami asks the Buddha to teach the bhikkunis. The small number of “bhikkhuni suttas” contrasted with the frequent references to the bhikkunis throughout the Pali Canon suggests a deliberate suppression of suttas in which bhikkunis were featured prominently, presumably due to the obvious gender bias of the First Buddhist Council. The insights of these “wise women” have been lost forever.