For Wayne

The phrase Buddha-nature sounds reassuring. And in a sense, it is — but it can also be misleading. Buddha-nature is also one of the most easily misunderstood Buddhist teachings.

It is liberating precisely because it is not what we usually want it to be.

On the one hand, Buddha-nature has been experienced by countless practitioners as profoundly freeing. It answers a deep, often unspoken anxiety: Is awakening really possible for someone like me? Not in theory, not for sages or saints, but here, now, in this confused and imperfect life. Buddha-nature says: yes — and not because you are special, but because awakening does not have to be manufactured from scratch.

On the other hand, the same teaching has repeatedly been distorted. In modern contexts especially, Buddha-nature is often misunderstood in three common ways.

First, it is taken to be an inner divinity — a kind of hidden spiritual jewel, a soul in Buddhist clothing. Something pure and personal tucked away inside us, waiting to be rediscovered. This reading smuggles back in exactly what the Buddha worked so hard to dismantle.

Second, Buddha-nature is sometimes reduced to a form of optimism therapy. Everyone is basically good. Everything will work out. Don’t worry too much — you’re already enlightened in some deep sense. That version may be comforting, but it empties the teaching of its sharpness, its discipline, and its demand for transformation.

Third, and more subtly, Buddha-nature is sometimes treated as crypto-Vedānta — a way of reintroducing a permanent Self while insisting that it isn’t really a Self. Here Buddhism is made to sound as though it ultimately agrees with non-dual Hindu metaphysics, only using different words. This reading may appear philosophically sophisticated, but it violates the historical and doctrinal core of Buddhism.

So if Buddha-nature is not an inner soul, a therapeutic slogan, or Vedānta in disguise, then what is it?

To understand that, we need to ask the question Buddha-nature actually answers. And that question is not “Who am I, really?” It is more austere, and more radical:

What makes awakening possible at all?

Not why it is desirable, or how to achieve it, but how liberation can even make sense in a world where there is no permanent self, no creator, no eternal substance, and no metaphysical ground. If everything conditioned arises and passes away, if even consciousness itself is impermanent, then what is it that awakens? And what is it that is freed?

Buddha-nature is not a thing that answers this question. It is not a hidden object, a metaphysical entity, or a refined essence. It is not something you possess. It is not something to which you can point.

Instead, Buddha-nature names a fact about the structure of experience and liberation: that awakening is possible because confusion is not intrinsic, obscuration is removable, and the unconditioned can be realized without being fabricated.

In other words, liberation does not come from adding something new to experience, but from seeing clearly what was never dependent on confusion in the first place.

In this talk I will show how this understanding unfolds historically and philosophically — moving from early Buddhism, where the problem is already present, through Mahāyāna reflections on emptiness and compassion, Yogācāra analyses of mind and continuity, into the Buddha-nature texts themselves, and finally into tantric and Dzogchen expressions that speak unapologetically of primordial awareness — before returning, at the end, to the modern world and the question of what this teaching actually asks of us now.

Buddha-nature does not flatter us. But it does something better. It tells us why awakening is neither miraculous nor illusory.

Once we strip away the popular misunderstandings, Buddha-nature turns out not to be an extra belief added onto Buddhism, but a response to a problem Buddhism itself creates.

The Buddha begins by removing nearly everything people normally rely on to make sense of liberation. There is no identifiable self that survives unchanged through time. There is no creative soul placed in the world from outside. There is no eternal substance underlying appearances. Everything conditioned arises and passes away, “moment by moment.” Consciousness itself is impermanent.

And yet the Buddha does not conclude that liberation is meaningless or illusory. He does not say that awakening is a poetic metaphor or a psychological coping mechanism. Liberation is real, irreversible, and final.

But if there is no enduring self-entity and no eternal ground, then what continues, what awakens, and what is liberated?

Early Buddhism does not answer this by smuggling in a hidden being. Instead, it holds together several strands that only later thinkers fully articulate.

First, there is the karmic continuity. Intentions have consequences that unfold across time, and even across lifetimes. This continuity is real, but it is not personal identity. Something continues, but it is not a self. The Buddha repeatedly refuses to explain this in metaphysical terms, yet he does not deny it.

Second, there is the Buddha’s insistence on the deathless (amata). Nirvāṇa is not simply the cessation of suffering in a psychological sense; it is described as unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned. These words rule out the idea that liberation is something fabricated by practice in the same way a skill or a habit is fabricated. It is real.

And third, nirvāṇa is not annihilation. The Buddha is explicit about this. Liberation is not the destruction of something real, nor the collapse of the person into nothingness. The Middle Way is defined precisely by rejecting both extremes.

These claims generate a tension that cannot be ignored. If nothing permanent exists, then liberation cannot mean the salvation of a soul. But if liberation is not annihilation, then something about experience must be capable of awakening without being a permanent thing.

This is the pressure point where Buddha-nature later emerges.

Buddha-nature does not appear as a sudden revelation or a doctrinal invention. It appears as a clarification. As Buddhism reflects on its own commitments — non-self, interdependent origination, karmic continuity, and the unconditioned — it becomes necessary to say something more precise about how awakening is possible at all.

One danger is nihilism: the view that nothing ultimately matters, that liberation collapses into nothingness, that practice is merely provisional. The other danger is eternalism: the temptation to reintroduce a hidden self, a “cosmic consciousness,” or a permanent essence under a different name.

Buddha-nature holds the line between both extremes. It does not retreat from the Buddha’s fundamental insights, but remains faithful to them — even when they lead us into uncomfortable philosophical territory.

The doctrine of Buddha nature does not clarify who we are, but why awakening is not a contradiction in an impermanent world.

Before the term Buddha-nature appears, the early Buddhist texts establish a framework that makes something like it hard to avoid. Not by asserting a hidden essence, but by the careful way they speak about liberation itself.

Let’s begin with the Buddha’s description of nirvāṇa.

Nirvāṇa is defined negatively — not as something added to experience, but as something fundamentally unlike conditioned phenomena. It is described as unborn, unbecome, unmade, unconditioned. These are not poetic flourishes. They are philosophical boundary markers. They tell us that liberation is not something fabricated out of causes in the same way thoughts, emotions, or even meditative states are fabricated.

This creates a logical tension. If everything conditioned arises and passes away, and if practice itself consists of conditioned activities — ethical discipline, meditation, insight — then liberation cannot simply be the product of those activities in the way a skill is learned or a habit is formed. Practice clears the way, but it cannot manufacture the unconditioned.

Early Buddhism does not resolve this tension by explaining what nirvāṇa is. It resolves it by refusing to explain it away. Liberation is real, attainable, and not fabricated.

Closely related to this is the Buddha’s teaching on the luminous mind (pabhassara citta). The Buddha says that mind is luminous, but that it is defiled by adventitious defilements. The language here is precise. The mind is not created by defilements, nor permanently stained by them. The defilements are āgantuka — arrivals, visitors.

This is not yet Buddha-nature, but it is already doing similar work. The mind is capable of clarity because confusion is not intrinsic. Liberation replaces the mind with something else, but removes what does not belong to it.

This distinction creates space for the idea that awakening is a matter of uncovering rather than constructing — without implying that there is a pure self hidden inside. The Canon never says that mind is pure in an absolute sense. It says it is luminous and obscurable. That difference is everything.

Now consider the question of continuity.

The Buddha consistently denies a permanent self. No aggregate, no combination of aggregates, no consciousness, no knower can rightly be called “I” or “mine.” And yet he also denies annihilation. Karma continues. Intentions bear fruit. Liberation is meaningful precisely because something is freed from bondage.

To hold these strands together, early Buddhism works with the idea of a stream — a continuity of mental events that is neither substantial nor void. This mindstream is not a metaphysical entity. It has no essence. It exists only as ongoing conditioned process. And yet it is sufficient to account for responsibility, rebirth, and liberation.

Consider the river. The river has a nature; it consists of water that flows. It is defined by its banks, and by its course. And yet, the water that constitutes the river is continuously changing. The banks that define its boundaries are constantly eroding. The width and direction of the river is constantly changing. If one looks at the river deeply suddenly one realizes that the river is not identical with anything identifiable. Not one thing about the river is permanent. And yet there it is, experienced for all that. It is not a thing, it is a process. The mindstream is like that.

This is a deeply restrained position. The Buddha does not explain continuity by appealing to a carrier-substance. He explains it functionally. Causes give rise to effects. Patterns continue without identity. The stream flows without a self steering it, like a river.

What is crucial here is that liberation occurs within this stream, but is not identical with it. The mindstream can be purified, transformed, and ultimately freed — but nirvāṇa itself is not another moment in the stream. It is not the final refinement of conditioned consciousness. It is the cessation of the ignorance that binds the stream.

This brings us to what early Buddhism does not say.

It does not say that there is an eternal Self underlying experience. It does not say that there is a latent Buddha-essence residing in beings as a metaphysical substance. It does not say that consciousness itself is ultimate or immortal.

But it also does not say that awakening is manufactured out of nothing. It does not say that liberation is a psychological construction, or a socially useful illusion, or a convenient way of speaking about reduced suffering.

Instead, the Canon holds a carefully balanced position: awakening is real, irreversible, and unconditioned — and yet it does not belong to any self, essence, or thing.

This balance is not accidental. It is the pressure that later Buddhist thinkers inherit. Buddha-nature does not appear because early Buddhism was vague or incomplete. It appears because early Buddhism was so disciplined in refusing easy answers that a deeper clarification became necessary.

Thus, the Buddha-nature teachings do not depart from early Buddhism, but attempt to make explicit — without breaking the original constraints — what early Buddhism already implies: that confusion is contingent, liberation is possible, and nothing eternal needs to be smuggled in for awakening to make sense.

What comes next, in the Mahāyāna, is not a reversal of this logic — but an effort to articulate it.

With the rise of Mahāyāna, the question that Buddha-nature will eventually answer becomes sharper, more unavoidable, and in some ways more dangerous. This is because Mahāyāna Buddhism radicalizes one of the Buddha’s central insights: emptiness.

Śūnyatā is not introduced as a new teaching, but as a deepening of interdependent origination. If things arise only in dependence on causes and conditions, then they lack any independent essence. And the Mahāyāna follows this logic all the way down.

All phenomena are empty — including consciousness, the path, even the teachings themselves. And finally, most provocatively, even nirvāṇa is empty.

This is a decisive move. It prevents the unconditioned from being reified into a metaphysical absolute. It ensures that liberation cannot become something one possesses, a place one arrives at, or a substance one merges with.

But if everything is empty, and emptiness itself is empty, then what remains? What makes awakening more than a conceptual rearrangement? What grounds compassion if there is no enduring being to save and no ultimate reality to rest in?

For many practitioners emptiness alone can feel destabilizing. This is why it was originally a secret teaching, reserved for advanced practitioners. It can sound like a sophisticated form of nihilism. The more rigorously emptiness is applied, the more the question presses: empty of what, exactly — and to what end?

This is where compassion enters the picture, not as a sentiment, but as a logical necessity.

Mahāyāna does not merely affirm compassion as a virtue. It builds the entire path around the bodhisattva vow: the commitment to awaken for the sake of all beings. And that vow presupposes that awakening is possible for all beings, without exception.

If some beings were permanently incapable of awakening, the bodhisattva vow would collapse into tragedy or delusion. Compassion would become either naive optimism or cosmic futility. The Mahāyāna refutes both.

So the doctrine of universal compassion demands a doctrine of universal awakening, as an ethical requirement. You cannot commit yourself to the liberation of all beings unless liberation is available to all in principle

This is where Buddha-nature begins to emerge. Emptiness clears away false grounds; compassion demands that something remain possible.

Crucially, this “something” cannot be a hidden substance or metaphysical essence. That would violate emptiness. But it also cannot be mere nothingness. That would undermine the path.

So Mahāyāna thinkers speak of emptiness not as a void, but as openness. Not as the absence of reality, but as the absence of obstruction. Things are empty not because they are unreal, but because they are not fixed, frozen, or sealed off from transformation.

Emptiness becomes possibility. Because things lack inherent essence, they can change. Because confusion is not intrinsic, it can cease. Because no being is defined finally, awakening becomes possible.

Sometimes this is called the “groundless ground.” Not a metaphysical foundation, but a refusal of foundations that paradoxically allows everything else to stand. There is no bedrock beneath experience — and precisely for that reason, experience is not trapped.

The doctrine of Buddha-nature will eventually give this insight a name and a language. Emptiness dismantles every attempt to absolutize the conditioned. Compassion insists that liberation is not a private exception. Between them, a space opens in which awakening can be universal without being eternal, and possible without being guaranteed.

Mahāyāna does not solve the problem the Buddha left us. It sharpens it. And in doing so, it makes the emergence of Buddha-nature not only intelligible, but almost inevitable.

Buddha-nature finally steps onto the stage in a family of texts known collectively as the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras. And it is important to see why these texts appear when they do, and for whom they were written.

They do not arise because Buddhism suddenly decided to change its mind about non-self. They arise because certain misunderstandings had become too persistent to ignore.

One such misunderstanding is nihilism. As emptiness was taken more seriously, some practitioners began to hear the teaching as a denial not only of essence, but of meaning itself. If everything is empty, then perhaps nothing truly matters. If all phenomena lack inherent nature, then perhaps liberation itself is only a provisional idea.

The Tathāgatagarbha texts respond directly to this. They insist that awakening is not negated by emptiness — and that something about liberation is stable, reliable, and universal, even though it is not a thing.

At the same time, these texts speak to devotional and faith-based cultures. As Buddhism spread, it encountered audiences for whom abstract negation was not a workable entry point. The language of Buddha-nature says: the path is real, awakening is possible, and no being is excluded.

This brings us to the core claims of the Tathāgatagarbha tradition.

The first is the most famous: all beings possess Buddha-nature. It is a structural claim. No being is constituted in such a way that awakening is impossible. There are no ontological outcasts.

Second, the texts insist that defilements are removable. Ignorance, craving, and aversion are powerful, deeply ingrained, and endlessly creative — but they are not essential. They obscure; they do not define. This repeats what early Buddhism already suggested with the idea of adventitious defilements.

And third, awakening is described as revelatory rather than creative. Buddhahood is not assembled out of parts. It is uncovered when obscurations dissipate. Practice clears; it does not construct. The Tathāgata is not produced; it is revealed.

To communicate this, the texts rely heavily on metaphor.

We are told of gold hidden in ore — precious, unchanged, but temporarily inaccessible. Or honey surrounded by bees — sweet, nourishing, but dangerous to approach without care. Or a seed, a womb, an embryo — something already present, waiting for conditions to mature.

These images are evocative, memorable, and pedagogically effective. They reassure practitioners who fear they lack the right spiritual equipment. They say: nothing essential is missing.

But metaphors are also treacherous.

Taken literally, these images suggest a substance — a pure core, an inner object, a metaphysical nugget lodged inside the person. And this is exactly what the doctrine does not intend. The gold is not a thing hidden somewhere. The embryo is not a soul waiting to be born. These are images for obscuration and disclosure, not blueprints of inner anatomy.

The texts themselves warn against literalization. Their language is deliberately bold because the danger they are countering — nihilism — is equally bold. They are willing to risk misunderstanding in order to prevent despair.

This brings us to the question: is Buddha-nature a Self?

On the surface, some passages seem to flirt with that idea. Terms like permanence, stability, even “self” appear, especially in certain versions of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra. This has understandably raised eyebrows.

But when read carefully, the texts are explicit: Buddha-nature is not a personal self, not an ego, not an agent that owns experience. The language of “self” is used strategically, not ontologically. It is meant to counteract fear — the fear that liberation means obliteration.

What is being denied is not non-self, but annihilationism. The texts are not saying, “There really is a self after all.” They are saying, “Awakening does not erase reality.”

This distinction matters. Buddha-nature is not what you are as a person. It is not your identity. It is not something you can point to and say, “That’s me.” It names the fact that awakening is not the destruction of something real, but the removal of what never truly belonged.

In this way, the Tathāgatagarbha sutras walk a narrow line. On one side lies eternalism: the temptation to turn Buddha-nature into a metaphysical essence. On the other lies nihilism: the fear that emptiness leaves nothing worth realizing.

Their language is strong because the path between these extremes is narrow. They speak in affirmations not to undo emptiness, but to prevent emptiness from being misheard.

Buddha-nature, as these texts present it, is not a hidden treasure inside us. It is the assurance that awakening is not a cosmic accident — and that the Dharma does not culminate in nothing at all.

As the doctrine of Buddha-nature develops, it encounters a serious technical problem — one that cannot be solved by reassurance or metaphor alone. This problem concerns continuity. If there is no self, no soul, and no permanent essence, then how exactly do karmic patterns persist? And how does awakening occur within a stream of experience that is constantly changing?

This is where the Yogācāra tradition enters the conversation.

Yogācāra thinkers introduce the notion of ālaya-vijñāna, usually translated as the “storehouse consciousness.” This is not a hidden self, and it is not an eternal mind. It is a way of explaining continuity without invoking a soul.

The ālaya is said to function as a repository — not of memories in a psychological sense, but of karmic tendencies, dispositions, and latent potentials. Actions leave traces; those traces condition future experience. The storehouse is simply the name given to this ongoing causal process.

Crucially, this continuity is impersonal. The ālaya does not decide, intend, or observe. It does not stand apart from experience. It arises “moment by moment” in dependence on conditions, just like everything else in saṃsāra. Its purpose is explanatory, not metaphysical.

In this sense, Yogācāra radicalizes early Buddhist restraint. It refuses both the idea of a transmigrating self and the idea that karma somehow operates without any continuity at all. The storehouse consciousness is continuity without identity — process without owner.

But once this framework is in place, a new question emerges: how does this storehouse relate to Buddha-nature?

Here the tradition divides, not into opposing camps, but into two interpretive emphases.

The first reading says that when the ālaya is fully purified — when ignorance and karmic imprints are exhausted — it is transformed into wisdom. On this view, what we call Buddhahood is the complete clarification of the mindstream itself. Nothing new appears; nothing eternal is revealed. The same process, freed from distortion, is now seen as awakened knowing.

The second reading is more cautious. It insists that the ālaya does not transform into wisdom — it ceases. When the conditions that sustain the storehouse collapse, what is revealed is not a refined consciousness, but something categorically different. Not another level of mind, but the non-fabricated knowing that Buddha-nature points toward.

Both readings attempt to preserve the same insight: awakening does not involve the survival of a soul. But they disagree on whether the mindstream itself can be the final vehicle of liberation.

This disagreement matters because it exposes a danger Yogācāra is acutely aware of reification of consciousness.

If one is not careful, the storehouse consciousness begins to sound like exactly what Buddhism has always rejected — a subtle, enduring self disguised as process. A cosmic mind. A universal knower. Yogācāra texts repeatedly warn against this. Consciousness, no matter how subtle, remains conditioned. It arises. It ceases. It is empty.

Even the ālaya is empty.

Yogācāra is not saying that everything is consciousness. It is saying that our experience is mediated by consciousness — and that mistaking that mediation for an ultimate ground is precisely the error that binds us.

So the tradition uses the language of mind to explain continuity, but it refuses to let mind become absolute. It explains karmic persistence without granting it metaphysical status. And it insists that liberation cannot be the perfection of consciousness, but the ending of ignorance about it.

In this way, Yogācāra sharpens the distinction we saw earlier between mindstream and Buddha-nature. The mindstream — even in its subtlest form — belongs to the conditioned order. Buddha-nature does not.

Whether one says that the ālaya is transformed or that it ceases, the conclusion is the same: awakening is not the eternalization of mind. It is the collapse of confusion that made mind appear as something it never truly was.

Yogācāra does not replace emptiness with consciousness. It shows that even consciousness is empty — and that emptiness is precisely what makes awakening possible without leaving anything behind to cling to.

This sets the stage for the final turn, where Buddha-nature will be spoken of not as a function of mind at all, but as the recognition of what is present when fabrication finally stops.

As Buddhism enters the Tibetan world, the question of Buddha-nature reaches its most explicit and, in some ways, most dangerous articulation. Dangerous not because it abandons restraint, but because it speaks without euphemism. Tantra and Dzogchen do not merely imply Buddha-nature — they point to it directly.

Here Buddha-nature is spoken of as primordial awareness: in Dzogchen terms, rigpa — pristine, non-dual knowing. This awareness is described as empty, yet cognizant; without form, yet vividly present; not produced, not destroyed, and not improved by practice.

This language can be shocking if we are not prepared for it. It sounds absolute. It sounds final. And without context, it can sound suspiciously like a metaphysical claim.

But what is being pointed to here is not a substance, not a cosmic mind, and not a background consciousness watching the world unfold. Rigpa is not an entity behind experience. It is the immediate knowing of experience when grasping collapses. Empty of essence, yet capable of knowing.

In these traditions, Buddha-nature is no longer spoken of primarily as a capacity that beings possess, but as a reality that is already present. And this introduces an important distinction.

Some traditions emphasize Buddha-nature as potential. On this view, beings are like seeds that can grow into Buddhahood if conditions are right. Practice cultivates that potential until it matures.

Other traditions — especially Dzogchen — emphasize Buddha-nature as already present. Not latent in the sense of dormant, but present in the way the sky is present even when obscured by clouds. Practice does not cause awakening; it reveals it.

These are not contradictory positions so much as different pedagogical angles. The language of potential protects against complacency. The language of presence protects against despair. Both aim at the same realization: awakening is possible without being fabricated.

This brings us to the question of sudden versus gradual realization.

From the Tibetan perspective, the path is often described as gradual in method but sudden in realization. Obscurations — karmic habits, emotional reactivity, conceptual fixation — are removed over time. Ethics, meditation, and insight are not bypassed. They are indispensable.

But what they culminate in is not something newly produced. The moment of recognition is sudden because what is recognized was never absent. There is no temporal process by which Buddha-nature comes into being. There is only the moment when non-recognition ends.

This distinction matters. Without it, one either imagines enlightenment as a future achievement or mistakes intellectual insight for realization. In Tibetan traditions awakening is neither.

Yet precisely because this language is so direct, it carries real dangers.

One danger is spiritual narcissism. If Buddha-nature is already present, one might conclude that one’s ordinary thoughts, preferences, and impulses are already expressions of enlightenment. This collapses discernment and erases the difference between wisdom and habit.

Another danger is complacency — the idea that since one is “already enlightened,” there is nothing to practice, purify, or restrain. History shows that this misunderstanding has done real harm.

Authentic Tibetan lineages are acutely aware of these risks, and they guard against them carefully. Direct pointing-out instructions are not given casually. They are embedded within rigorous ethical training, prolonged discipline, and a relational context between teacher and student.

Moreover, these traditions emphasize a crucial distinction: recognition is different from stabilization. One may glimpse rigpa and still be thoroughly ruled by habits. Practice after recognition is not redundant; it is essential. It integrates insight into life.

Perhaps most importantly, Tibetan teachings repeatedly insist that genuine realization manifests as humility, compassion, and restraint — not as grandiosity or self-certainty. If recognition leads to arrogance, it is not recognition.

In this way, Tantra and Dzogchen intensify the caution of early Buddhism. They speak directly because indirect language has done its work — but they surround that directness with safeguards.

Buddha-nature here is neither a promise nor a possession. It is not something you can claim. It is something that undermines any and all claims.

Seen rightly, the Tibetan synthesis does not overturn emptiness, Yogācāra, or the Tathāgatagarbha teachings. It brings their implications to a sharp point. If awakening is unfabricated, if defilements are adventitious, and if mind itself is empty, then recognition must be possible without manufacture.

But that possibility comes with responsibility.

To say that Buddha-nature is already present is not to say that we are finished. It is to say that the work of the path is not self-creation, but self-deception undone.

And that may be the most demanding claim Buddhism makes.

At this stage, it becomes important to say what Buddha-nature is not. Because nearly every misunderstanding of this teaching comes from mistaking it for something Buddhism has consistently refuted.

Buddha-nature is not a soul. It is not a personal essence that survives unchanged through time. It does not belong to you, it does not define your identity, and it does not stand behind experience as an owner or observer. The Buddha rejected the soul doctrine not because he wanted to deny meaning, but because the very idea of a soul smuggles in permanence, control, and possession — precisely the things that bind us.

Buddha-nature is also not a “cosmic consciousness.” It is not a universal mind in which individual minds participate. It is not a background awareness watching the universe unfold. Consciousness, in all Buddhist systems, is conditioned. It arises. It ceases. It depends. To absolutize consciousness is simply to move the self one level higher and call it something nobler.

Nor is Buddha-nature God in disguise. It does not create the world, govern moral order, or stand outside time dispensing grace. Buddhism consistently refuses the idea that liberation depends on an external agency. Awakening is not bestowed. It is realized. To turn Buddha-nature into a divine principle is to undo the Buddha’s most radical insight: that freedom does not come from outside experience.

Finally, Buddha-nature is not a metaphysical substance. It is not an underlying stuff out of which phenomena are made. It does not persist unchanged beneath appearances. Any attempt to describe it as a “ground of being” in a substantial sense runs straight into the very reification Buddhism exists to prevent.

So why does Buddhism refuse these options so firmly?

Because each of them turns liberation into something graspable. A soul can be possessed. A cosmic mind can be merged with. A god can be appeased. A substance can be clung to. And wherever grasping survives, suffering survives.

But refusing these options does not collapse meaning.

Meaning does not depend on permanence. It depends on intelligibility. Liberation matters not because something eternal is saved, but because confusion can end. Compassion matters not because beings have immortal cores, but because suffering is real and unnecessary. Practice matters not because we are becoming something divine, but because ignorance is removable.

Buddha-nature names this possibility without turning it into an object.

It says: awakening is possible without a soul. Freedom is real without a god. Meaning survives without metaphysical guarantees. The path holds because reality is not closed.

If anything, this refusal deepens meaning. It places responsibility back where Buddhism has always placed it — not in a hidden essence, but in clear seeing. Not in what we are, but in what we mistake ourselves to be.

Buddha-nature, rightly understood, does not comfort the ego. It removes its last refuge. And in doing so, it leaves something far more durable in its place: the possibility of awakening that does not depend on illusion.

Up to this point, Buddha-nature may sound abstract — a solution to a philosophical problem, a way of holding together non-self and liberation without contradiction. But the teaching only matters if it changes how we practice.

Let’s begin with meditation.

If awakening is not fabricated, then meditation cannot be a self-constructed. We are not trying to manufacture purity, nor to assemble enlightenment piece by piece. Practice is better understood as uncovering — removing what obscures rather than adding what is missing.

This shifts the tone of meditation in a subtle but important way. Effort remains necessary. Discipline remains non-negotiable. But the effort is no longer anxious. One is not straining to become worthy. One is learning to stop interfering.

This does not mean passivity. Trust in Buddha-nature is no excuse for laziness. The obscurations are real. Habits do not dissolve on their own. What changes is the emotional background of practice. Confidence replaces desperation. Patience replaces self-judgment. You practice not because you are broken, but because confusion has momentum.

In this way, Buddha-nature undercuts both spiritual ambition and spiritual despair. It removes the fantasy that enlightenment is an achievement that proves your value — and it removes the fear that you lack what is required.

The same realism carries over into ethics.

If all beings possess Buddha-nature, then ethical regard is not based on sentiment, preference, or likeness to ourselves. It is grounded in capacity. Every being suffers because every being is confused — and every being can awaken because confusion is not intrinsic.

This prevents compassion from collapsing into mere empathy. Compassion is not about liking others or feeling warmly toward them. It is about recognizing that suffering is unnecessary, and that no being is constitutionally excluded from freedom.

This is why Buddhist ethics does not depend on moral outrage or moral superiority. It depends on understanding. Harm is wrong not because it violates a divine law, but because it reinforces confusion — in oneself and in others. To act ethically is to align with the possibility of awakening, not to prove one’s virtue.

Seen this way, compassion becomes a form of realism. It does not deny cruelty, ignorance, or destructiveness. It refuses to define beings by them. Even those who cause harm are not reduced to that harm. Their capacity for awakening remains, however obscured.

This is not indulgence. It does not mean tolerating injustice or abandoning discernment. It means that even when firm action is required, hatred is not.

Finally, Buddha-nature reshapes the role of faith — or, in Buddhist terms, śraddhā.

Śraddhā is not belief in doctrines. It is not assent to metaphysical claims. It is confidence — first, in the path, and second, in the possibility of one’s own awakening.

Confidence in the path means trusting that practice is not futile. That liberation is not a myth. That the teachings are not merely therapeutic narratives, but descriptions of something that can be known.

Confidence in oneself is more delicate. It does not mean self-esteem or self-affirmation. It does not mean believing that one’s opinions are enlightened. It means trusting that awakening does not require becoming someone else.

This is confidence without ego. You trust the possibility of awakening without claiming ownership of it. You rely on Buddha-nature without turning it into an identity.

In this way, Buddha-nature supports practice without corrupting it. It does not tell you that you are already finished. It tells you that the work you are doing is not in vain — and that what awakens was never dependent on your confusion in the first place.

That may not sound dramatic. But for sustained practice, it makes all the difference.

When Buddha-nature enters the modern Western world, it does not arrive in neutral territory. It meets a culture already saturated with strong assumptions about selfhood, meaning, and value — and those assumptions shape how the teaching is heard.

One common misunderstanding is romanticism. Buddha-nature is taken as a poetic affirmation of uniqueness, creativity, or personal authenticity. It becomes a way of saying that each individual is secretly radiant, special, or spiritually gifted. While this reading sounds positive, it quietly recentres the self — the very move Buddhism is trying to undo.

Another distortion is psychological reductionism. Buddha-nature is recast as mental health, emotional regulation, or self-acceptance. The path becomes a therapeutic technique, and awakening becomes a stable, well-adjusted personality. Psychology has much to offer Buddhism, but when Buddha-nature is reduced to well-being, its ontological depth is lost. Liberation is not simply a better relationship with one’s thoughts.

These misunderstandings flourish because the modern world is already under strain.

Many people live with a pervasive sense of alienation — from community, from tradition, from nature, and often from themselves. Identity is unstable, roles are provisional, and meaning feels outsourced to systems that do not care about meaning at all.

Alongside this is technological dislocation. Our lives are mediated by abstract systems that operate faster than understanding and at scales no individual can grasp. Attention is fragmented. Experience is flattened. The sense that reality itself is coherent begins to erode.

And hovering behind both is post-religious nihilism. The old metaphysical certainties are no longer persuasive, but nothing equally deep has taken their place. Many people oscillate between longing for meaning and suspicion of anything that claims to offer it.

In this context, Buddha-nature matters precisely because it does not offer a new belief system to replace the old ones. It does not promise cosmic reassurance or personal exceptionalism. Its answer is quieter — and more radical.

It says that awakening is possible not because the world is secretly guided, not because we have immortal souls, and not because history is moving toward redemption. Awakening is possible because reality itself is not broken.

Confusion arises. Suffering arises. Systems distort experience. But none of this is intrinsic. None of it seals the nature of experience finally. There is no metaphysical damage at the core of things.

This is not optimism. It is not hope in the usual sense. It does not predict outcomes or guarantee progress. It simply refuses the conclusion that meaning has collapsed beyond repair.

Buddha-nature offers a way of affirming depth without illusion. It allows seriousness without dogma, and confidence without metaphysics. In a world suspicious of absolutes and exhausted by relativism, it suggests that clarity is possible without certainty, and liberation without guarantees.

That may not sound like much. But in a time when many feel that reality itself has gone wrong, it is a profound claim: the path is open because nothing essential is missing.

As we come to the end of this exploration, it may be helpful to let go of the idea that Buddha-nature is offering us something. It is not a promise about the future. It is not a consolation prize for difficult lives. And it is not a guarantee that everything will turn out the way we hope.

Buddha-nature is quieter than that. It is a fact of the path — one that only becomes visible when we stop asking Buddhism to reassure us.

It does not say that awakening will happen. It says that awakening is possible. And it does not ground that possibility in faith, identity, or metaphysics, but in the nature of experience itself. Confusion arises, but it does not define. Suffering appears, but it is not essential. Nothing about being human makes liberation impossible.

This reframes practice in a subtle but demanding way.

Practice does not make you worthy of awakening. You are not earning something through effort, virtue, or endurance. Practice makes you honest about how confusion operates and how grasping distorts experience, and about how much of what we take to be “self” is a series of mutually dependent habits.

When that honesty deepens, something unexpected happens. The struggle to become someone else begins to relax. The demand to justify one’s existence loosens. And in that loosening, recognition becomes possible.

What awakens is not a perfected version of the person. It is not a refined identity, a spiritual personality, or a polished self-image. What awakens is the capacity to know experience without distortion — a capacity that was never absent, only obscured.

This is why the tradition so often uses the image of clouds and sky. The sky does not improve when the clouds part. It does not arrive from elsewhere. It does not need to be repaired. When the clouds disperse, the sky is simply seen.

In the same way, Buddha-nature is not something added at the end of the path. It is what becomes evident when the habits that obscure clarity fall away.

Nothing mystical has to descend. Nothing metaphysical has to appear. Nothing essential has to be recovered.

What awakens was never lost — and was never owned.

If that sounds anticlimactic, it is because Buddhism does not trade in spectacle. It trades in release.

And release, when it comes, is not loud.

It is unmistakably simple.

Bibliography

Core Buddha-nature (Tathāgatagarbha) sutras

- Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra (Buddha-Womb Sutra)

- Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra (Lion’s Roar of Queen Śrīmālā)

- Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra (often the boldest “buddha-nature” language)

- Anūnatvāpūrṇatva-nirdeśa (Teaching on “Neither Increase nor Decrease”)

- Mahābherī Sūtra (Great Dharma Drum Sutra)

- Mahāmegha Sūtra (Great Cloud Sutra)

- Aṅgulimālīya Sūtra (Aṅgulimāla Sutra; Mahāyāna text)

- Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra (integrates tathāgatagarbha with Yogācāra concerns)

Commonly cited “related / bridge” sutras (often used in Tibetan and East Asian discussions)

These aren’t always exclusively “buddha-nature sutras,” but they’re regularly used to frame or support buddha-nature interpretation (especially alongside Yogācāra + emptiness):

- Buddhāvataṃsaka (Avataṃsaka / Flower Ornament) Sūtra

- Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra (key Yogācāra framing; often brought into buddha-nature debates)

Early canonical passages that later traditions read as “proto–buddha-nature”

The Nikāyas don’t teach “tathāgatagarbha” as a doctrine, but later Buddhists often point to luminous mind + adventitious defilements as doing similar work:

- AN 1.49–1.52 (Pabhassara / “Luminous Mind” passages

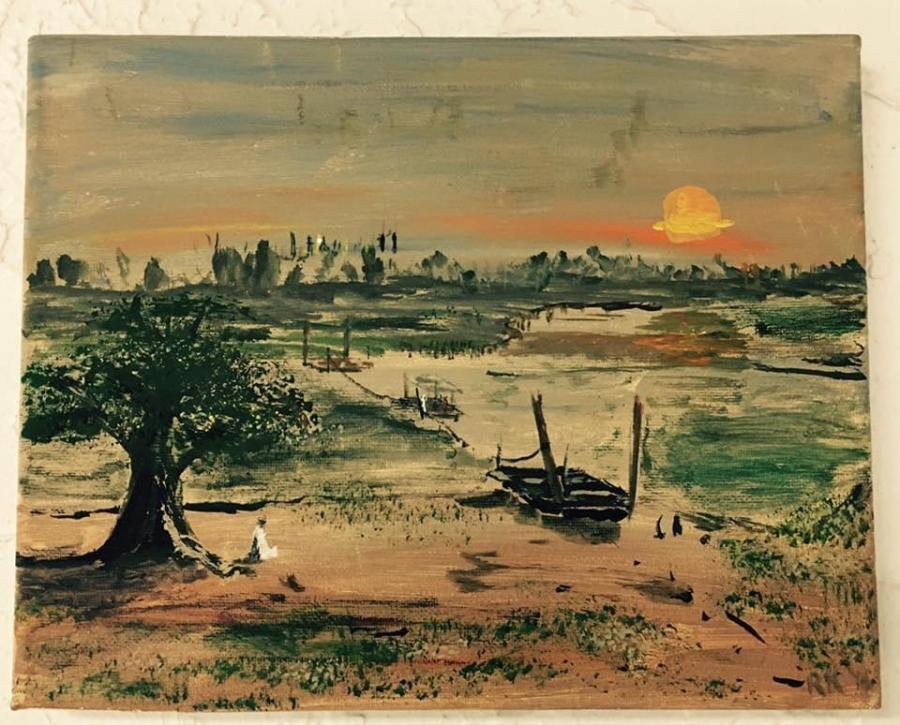

Credit

Painting is Siddhartha at the River Crossing, by Richard Keene (source: Reddit).